Public Q & A about Art Conservation and Museum Practices

Welcome to this digital resource intended to enhance your experience of Boucher: Conservation in a Park. This collaborative exhibition between the Timken Museum of Art and the Balboa Art Conservation Center (BACC) focuses on the public conservation of François Boucher’s Lovers in a Park (1758). Here, you'll find an ongoing conversation between the public, art conservators, and the Museum's own curatorial team.

Jump to: Week 1, Week 2, Week 3, Week 4, Week 5, Week 6, Week 7, Week 8, Week 9, Week 10

[Week 1 - October 20th Visitor Questions & Comments]

Question from Allison, R., "How does someone become a conservationist?"

- To become an art conservator, you first have to have a love of art and cultural objects. Next is the hands-on schooling, typically an undergrad degree in chemistry, art history, art, architecture, archeology or other related fields. Then a graduate degree in art conservation is the traditional pathway. There are only a handful of conservation graduate programs in the United States. (Alexis Miller, Head of Paintings Conservation at BACC)

✥ Learn more about the different conservation graduate programs within North America.

Question from Áine, K., “Is there a protocol to repairing / conserving artworks, or is each project on a case-by-case basis?”

- Each project is unique, we do change the protocols on a case-by-case basis. Even if you had two paintings from the same artist, it would be a completely different treatment for each painting. Of course it helps to have two artworks and familiarity with an artist, but each project is approached individually. (Alexis Miller, Head of Paintings Conservation at BACC)

Question from Áine, K.,“Are there conservationist ‘styles?’ Like would you be able to tell a conservation job was done by someone in particular by any signature style?”

- Not particular people, but approaches to conservation do vary by country or region. When considering conservation in painting, specifically: in Italy, large wall paintings will have large areas of loss (where the paint has gone missing due to damage or deterioration), and art conservators will fill the loss with a neutral tone. Another common practice in Italy is called “tratteggio” which is a blending of surrounding colors in a hatching pattern to fill a loss that mimics what may have been, especially at a distance, but is not an outright recreation. Upon close inspection it can be easily identified as being retouched. Other regional variations include how much varnish to leave on a painting, and what kinds of materials are used. America and England tend to embrace synthetics more than other regions, and Holland and Denmark embrace new adhesives. So, locations and regions can have certain conservation aesthetics, but there aren't any individual conservator's "styles" since we don't want to infuse a painting with our own DNA. (Alexis Miller, Head of Paintings Conservation at BACC)

Question from Áine, K., “Do you use the same materials / pigments as the original artwork was created in?”

- Yes and No. When an art conservator is recreating an area over paint loss, knowledge about when the painting was made helps to choose which paint pigments will match the best. For instance, if we know this is a 16th-century painting, then art history and knowledge of materials from that time tells us the blue in this painting is likely ultramarine and we can use that historical pigment as a reference for color matching when selecting pigments to do our in-painting. We will use synthetic ultramarine though, not the historical (and very expensive) lapis lazuli that ultramarine was originally made from, but a modern synthetic version. And conservators will not use oil paint. We use a special paint that is safe for the artwork and removable–meaning this in-painting could be safely undone by a conservator in the future, if need be. Another reason we don’t use oil paint is because it becomes hard, insoluble, and changes color over time. (Alexis Miller, Head of Paintings Conservation at BACC)

During the first week of treatment, conservators Bianca García and Alexis Miller begin by cleaning the surface of the painting with an aqueous solution, slowly and gently removing any dust or grime.

[Week 2 - October 27th Visitor Questions & Comments]

Question from Melissa S., “What is the procedure to conserve a part of the painting that is too brittle or delicate to work on?”

- As a painting conservator, first and foremost, we want to make a piece stable: no paint falling off, no fraying, or tearing of canvas. With something that’s really delicate, we would just have to approach it really carefully. It’s a lot about taking care to look and figure out what’s wrong before jumping into any sort of treatment. And so, knowledge and experience becomes important–knowledge of what the painting’s materials are, what adhesive to use (to stick loose paint back down), and what varnish to use, and how the different materials will react with each other becomes important when working with something delicate. And there have been paintings beyond repair. For instance, there have been paintings burnt in fires, or a large percentage of the painting is missing, or it hasn’t been safe to clean. It still takes knowledge of the materials, asking what is the painting made of, what needs to happen, and is it possible? (Alexis Miller, Head of Paintings Conservation at BACC)

Comment from Marie K., “Thank you for your amazing work!”

Question from Kendra S., “What has been your favorite painting to conserve and why?”

- I really don't have an answer. Favorite painting that I have ever conserved... I really enjoyed cleaning the Timken's painting by Gabriel Metsu, Girl Receiving a Letter (1658). The panel was in beautiful shape and just needed the removal of the varnish, which had yellowed with time. That treatment was a joy because it was small and jewel-like. That was wonderful. (Alexis Miller, Head of Paintings Conservation at BACC)

✥ Watch the transformation of Gabriel Metsu's Girl Receiving a Letter.

By the end of week 2, surface grime removal is complete. Conservators Alexis Miller and Bianca García have hand cleaned the entire surface of the painting using cotton swabs dipped in an aqueous solution. All dust, grime, and dirt has been lifted from the surface of the painting, and we are ready for the next step in the treatment process–varnish removal.

[Week 3 - November 3rd Visitor Questions & Comments]

Question from Shyrbel C., “When choosing art pieces to put on display what is being taken into consideration? How does one decide where to put pieces?”

- The Timken Museum of Art has a relatively small, but exceedingly fine collection of paintings, most of which are on public display at any given time. We have decided to organize this collection by national school (i.e., Russian icons, Italian/Spanish, Dutch/Flemish, French, and British/American), mostly because that division matches the number of galleries (5) we have designated for displaying these works. Other options might be to organize the collection thematically–that is, gather the portraits, landscapes, history paintings, etc. in a single space–or else group the works according to a more or less strict chronology. If we were to pursue one of these alternatives, however, we would likely face problems whenever a painting left the museum for loan at another institution, or is taken off view for conservation. This did not happen with the Boucher, obviously. We simply don’t have the depth to fill vacant spaces in all time periods or genres, whereas we usually have at least one or two paintings in storage from each of the national schools mentioned above. Lines of sight are important to any curatorial display. When placing works in the galleries, we always try to encourage viewers to make connections between the objects that they see there. So, in the French Gallery, we have organized the Rococo works together so that scanning the wall provides an opportunity to compare and contrast the stylistic approaches of several important artists at once. In the same way, we take into consideration what a visitor is likely to see first once they step into a given space. Take the case of Kehinde Wiley’s Equestrian Portrait of Tommaso of Savoy-Carignan (2015): that important loan commands its own wall in the Dutch/Flemish Gallery and is deliberately staged between the Timken’s Rembrandt and its portrait by Anthony van Dyck, who provided inspiration for Wiley’s majestic work. (Derrick Cartwright, Director of Curatorial Affairs at the Timken)

Question from Nicole G., “When do art conservators decide when it’s time to touch up the artwork?”

- There can be a variety of reasons for deciding to conserve a painting. If a painting exhibits structural issues like paint lifting, existing paint losses, tears in the canvas, or other pressing concerns, it would be important to address them because you would risk further damage and loss otherwise. When it comes to more aesthetic things like discolored varnish then it's a matter of how discolored it is, and whether we can wait on it. We prefer to extend or prolong the time period between treatments, so nothing is done every ten years–it's more like every 50+ years. Once an artwork becomes really discolored, for example, with the Boucher–it’s time–the varnish has started to yellow so much that it affects the interpretation and presentation of the artwork. Consequently, the Timken has decided that it is now the appropriate time to undertake a conservation treatment for this artwork. (Bianca Garcia, Associate Conservator of Paintings at BACC)

Question from Annie C., “What is your favorite historic pigment?”

- Lead tin yellow because of its unique and intriguing history. It was a commonly used yellow pigment popular in the 17th century until c.1750 when it mysteriously disappeared from use, only to reemerge in 1940 with a different formula. There’s nothing else like it, a peculiar vanishing yellow pigment! (Bianca Garcia, Associate Conservator of Paintings at BACC)

Week 3 begins with conservator Alexis Miller testing solvents for the next phase of treatment, which is varnish removal. The art conservators dip their cotton swabs into a custom solvent solution and remove inch by inch the aged yellowed varnish. Where the varnish is removed, the painting appears matte, with low contrast, since light is now scattering when it hits the raw surface of the painting.

[Week 4 - November 10th Visitor Questions & Comments]

Question from Kendra S., “What has been your favorite painting to conserve?”

- That’s such a hard question to answer. I love them all–they’re like my kids–all of them. I remember every single treatment. And sometimes it's not even about the artist, or what’s depicted, it’s about the challenge of the treatment. For instance, when I’ve mended a really big tear in a canvas and in-painted over the repair so the damage that was once there is now completely invisible—that brings me joy. (Bianca Garcia, Associate Conservator of Paintings at BACC)

Question from Kathleen B., “How do insects (or other pests) damage paintings?”

- There are a few ways that insects and pests can cause damage. In a painting, the structure on the back which is the stretcher (or strainer) is made of wood. Termites can invade and start eating the wood, compromising the stretcher’s integrity. If there’s a frame also made of wood, it's equally as susceptible to being eaten. In the painting itself, the canvas layer can also be susceptible because it's made of organic materials and can be food for insects. The paint layer however is not as tasty, but insects have been known to eat the canvas from the back. So, depending on how much they eat away, their damage could entail leaving a paint layer floating in the air without support. The paint is then vulnerable to collapsing and paint loss. So there’s different ways insects can affect paintings. (Bianca Garcia, Associate Conservator of Paintings at BACC)

[Week 5 - November 17th Visitor Questions & Comments]

Question from Scott H., “What is the most surprising thing you have discovered during a conservation project?”

- In 2008, I uncovered an artist’s signature when we were working on The Last Judgment, a rather large painting for the Mission San Luis Rey in Oceanside. At the time, no one knew who the artist was though the object could be dated to the mid- or late 18th century. The painting was previously restored in 1967, although not well, which resulted in a lumpy and rumpled surface. There was a lot of overpaint (when someone paints over damages, cracks, or paint loss) from that 1967 restoration–we suspected the canvas had been rolled, or folded–and we had to remove over 400 patches from the back of the canvas. When we removed the frame, we could see the bottom edge of the canvas was overpainted with a solid block of red paint. We found that to be rather interesting and examined it with infrared technology. And underneath all that overpaint, we were able to find the signature of the artist. We can surmise that the restorer wasn’t trained in the proper conservation techniques we use today and probably didn’t intend to hide the artist’s signature. After the discovery, we removed the overpaint using a microscope and scalpel to reveal the signature of José Joaquín Esquibel. The painting still hangs in the church today, on public view. (Alexis Miller, Head of Paintings Conservation at BACC)

Question from Annella R., “How do you adjust restoration styles over art movements, e.g. Baroque vs. Renaissance?”

- Our techniques used to fix paintings remain consistent despite the style of the object: We consolidate paint that's at risk of flaking or falling off. We remove grime. We may remove varnish. We fill and in-paint over areas of loss (places where the original pigment is missing). So, while the techniques do not change, it’s important to have art historical knowledge of what the painting should look like. What is a Baroque painting supposed to look like? What is a Cubist painting supposed to look like? Those two painting styles look completely different, not only because of the materials that they used but the ideas that the artist is trying to convey. An easy example would be whether we varnish an artwork. So for instance, let's say I'm working on a Picasso and it was never varnished, then I, as the art conservator, should never varnish it. With some artworks, a surface is supposed to be matte in one area and shiny in another area. It's about knowing the artwork, understanding different art styles, then using the right techniques and materials, and keeping it true to its original form. (Alexis Miller, Head of Paintings Conservation at BACC)

[Week 6 - November 24th Visitor Questions & Comments]

Question from Eilsey C., “How did they make a canvas that large?”

- The Boucher canvas is quite large, about 7.5 by just over 6 feet. The painting’s surface is made up of two pieces of fabric stitched together. If you look closely at the x-ray of the painting, you can see a vertical seam. This is because the weaving loom that was used to make the canvas was only so wide. Canvas can also vary in material and weave, depending on the country of origin. It may be made from natural fibers such as linen, cotton, hemp, or even jute (burlap) or ramie. Sometimes, a combination of these materials is used. Velázquez was known to work on patterned weaves (like woven tablecloth linen), thanks to its large size and availability for his use. (Bianca Garcia, Associate Conservator of Paintings at BACC)

Comment from Rikki O., “I’ve been coming here for over 10 years and this is my favorite painting. Thank you for all your hard work in preservation!”

[Week 7 - December 1st Visitor Questions & Comments]

Question from Jessica M., “Are art conservator techniques different?”

- Yes, conservation techniques can differ across countries. In general, conservators around the world share a common mission of preserving cultural heritage for the future, but how they do it is influenced by access to materials, education, training, and cultural values. In some countries, conservation work is overseen by a government office dedicated to preservation of cultural heritage while in other countries it is the responsibility of institutions and private individuals to care for their collections (as is the case in the United States). Aesthetic values can also be different depending on the country, contributing to a difference in art conservation techniques too. For instance, in Italy they like to be distinct with their corrections–when you get up close you can see where they have retouched the art, whereas in the US we try to make retouches appear seamless. (Bianca Garcia, Associate Conservator of Paintings at BACC)

[Week 8 - December 8th Visitor Questions & Comments]

Question from Nirmit K., “How do the paintings’ paint last so long?”

- Paintings don’t always last so long, and it takes certain circumstances to ensure an artwork’s longevity: good artist technique, good quality of materials, and good care. Let’s talk about each of these, what “good” is, and what could go wrong.

Good artist technique would mean the artist is using a tried-and-true painting process. For the Old Masters oil painting was a fine-tuned-, multi-step process: prime the canvas, build up with thin layers of oil paint, add a protective glossy varnish at the end. The Old Masters did not deviate or experiment much with this process, not in any way that would lead to the paint layers not sticking together, or the paint not drying properly, etc. All the layers of paint are compatible and lend themselves to a structurally sound painting. In contemporary art where we get into more experimentation of process and mixed media, there is a much higher chance that a painting’s structure is more fragile and potentially volatile.

Good material is about the quality of the pigments and oils used for painting. During the 17th century, you couldn’t go to an art store to buy tubes of paint. Many notable artists were part of guilds or workshops with apprentices that would grind the pigments and mix the paints themselves. This autonomy, most of the time, resulted in great control over the quality of the paint. However, if an artist worked with lower quality materials, whether to be frugal or experimental, it could lead to pigments on their palette that are light sensitive and end up fading or changing color overtime. Van Gogh is known to have used “geranium lake”–a vivid scarlet lake pigment derived from a synthetic dye–and it proved fugitive in daylight, fading his “pink roses” to white.

Good care is about good housekeeping. A painting’s environment is important. Changes in temperature, humidity, pests, and sunlight are all factors that could cause damage to a traditional oil painting, weaken its structure, or cause fading. A museum is a good place for a painting to be. It is a climate controlled space that is clear of pests, has minimal UV interaction, and is protected.

An artist using good technique and good quality materials ensures the longevity of their work. Proper care of the painting preserves it for our continued enjoyment. (Alexis Miller, Head of Paintings Conservation at BACC)

[Week 9 - December 15th Visitor Questions & Comments]

Question from Nam N., “How do you fix any mistakes in the conservation process? Like if you took too much off that it removed some of the original paint?”

- We do a lot of testing in the beginning to figure out what is the safest treatment for preserving the original paint layers. We use chemical analysis and knowledge of art materials to inform which solvents are used to safely remove exactly what we target for removal. We test on small, inconspicuous areas before proceeding with the full treatment. If any original paint, or color, appears on the testing swab we immediately stop and discard that option. Even in other steps of the treatment, even after testing, if what I proposed is no longer working, or the paint is not reacting as expected, then this treatment is no longer safe for the painting. We then have to stop and reevaluate our options. The trick is to pay attention and stop when you notice something is not quite right, or doesn’t follow expectations. You never shrug it off and just continue–that’s when mistakes are made. You have to ease into a treatment, always slowly and carefully. We don’t jump into the deep end of the pool in this profession. In our current stage of treating the Boucher where we are removing the old overpaint, we are using a very careful process. The overpaint is, for the most part, visually distinguishable from the original paint, but it is the same paint system, both made of oil paint, but the oil paints are different ages. The newer paint reacts to our thick gel solvent without lifting the original paint. All these different cleaning systems are tools in our toolbelt. (Bianca Garcia, Associate Conservator of Paintings at BACC)

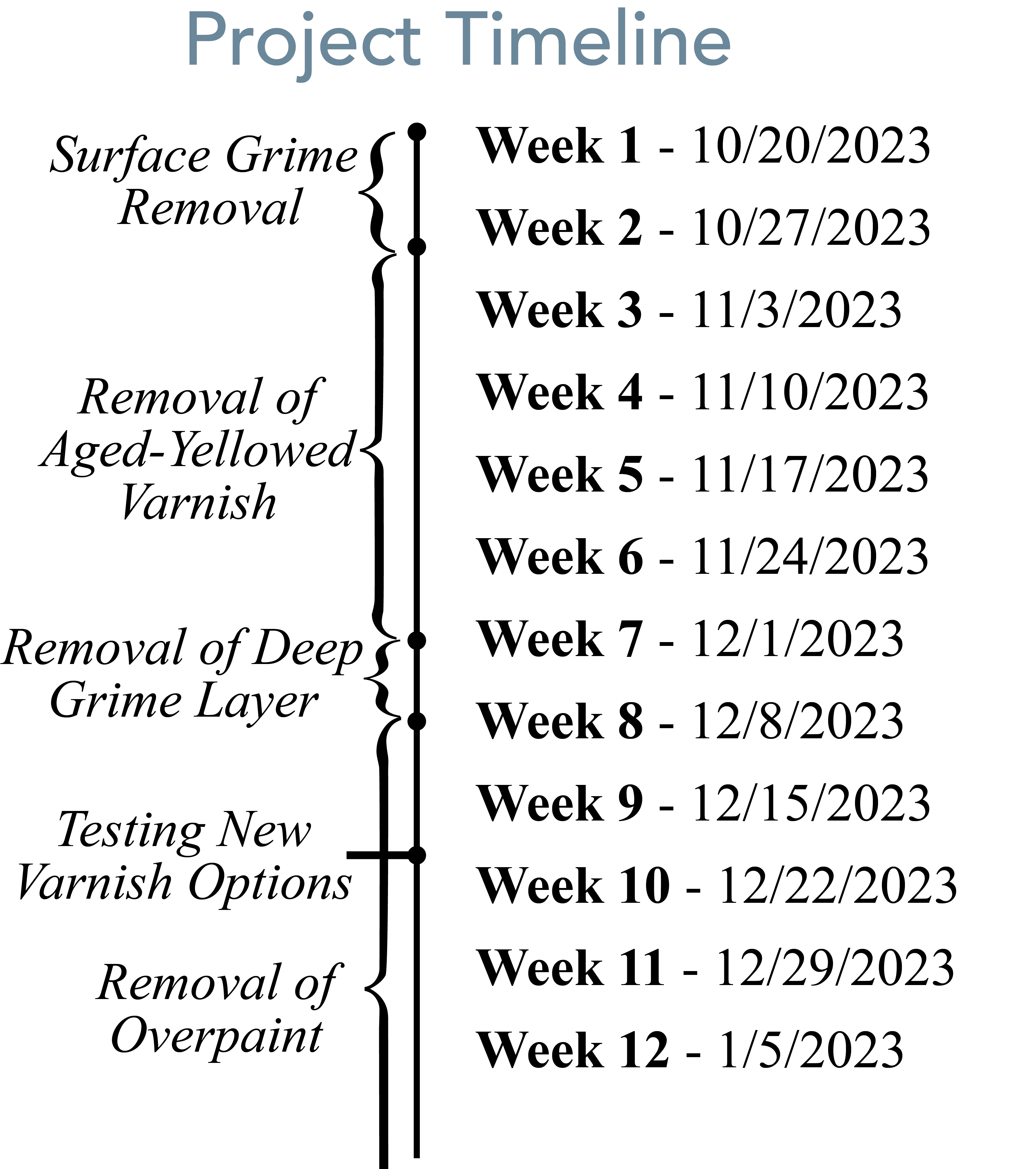

2-MONTH UPDATE:

Last week, the art conservators completed three surface cleanings. They dip cotton swabs into custom solvent solutions to clean the surface inch by inch. The three different cleanings are:

- Surface grime removal (2 weeks) - lifted away dust, grime, and dirt

- Varnish removal (5 weeks) - removed the old, aged, yellowed varnish

- Deep grime removal (1 week) - removed old trapped grime and old glue residue

Now the art conservators are working to remove sections of old “overpaint”. Overpaint is when someone paints over damages, cracks, or paint loss. It was done during a previous restoration, some time before the Timken acquired the painting. It is notable that the old overpaint was done using oil paint, which is not a practice art conservators would do today (today art conservators use synthetic pigments in a special compound that is safe for the artwork and removable). Oil paint is not easily removed and can change color as it oxidizes over time, so the art conservators are removing the sections of old overpaint where it is distracting and markedly discolored. To remove the overpaint, the art conservators cover the area with a thick gel solvent that works to loosen the paint, then they slowly and gently use a knife to scrape and lift away the paint.

[Week 10 - December 22nd Visitor Questions & Comments]

Question from Bradley M., “In the piece showing Jesus and twelve scenes from the passion, there are holes in the crown and other parts of the piece, as if jewels were originally inlaid but later ripped out. What happened?”

- In the large panel located in the Italian gallery, Madonna and Child and Two Angels, with Twelve Scenes from the Passion, attributed to the so-called Magdalene Master and an unknown Florentine artist, you are correct to notice that there are holes in the composition around the crown of the Virgin which likely originally had semi-precious stones set into them. This happened long before the painting entered the Timken’s collection. It is hard to say precisely when this took place. The work was painted in the early 14th century, however. It seems possible that this took place because they had some obvious value, but just as we can’t be certain who removed them, we also don’t know how valuable these inset gemstones actually were. (Derrick Cartwright, Director of Curatorial Affairs at the Timken)

✥ ✥ ✥ ✥ ✥

Have a question of your own for the Timken Museum of Art, the Balboa Art Conservation Center (BACC) or regarding our current exhibition, Boucher: Conservation in a Park? Complete our “Ask a Question” form. We will be accepting all questions, queries, and comments throughout our Boucher: Conservation in a Park project and publishing our dialogue here, at https://www.timkenmuseum.org/art/conservation/.