Work of the Week

by Derrick R. Cartwright, Director of Curatorial Affairs

Work of the Week #52

Frank L. Hope & Associates, The Timken Museum of Art, 1965

This weekly posting has been used to celebrate Timken paintings and sculpture. It seems fitting to mark a full year of “works of the week” with a note about the museum building itself which is another object of distinction.

Plans for a “free gallery” to house the extraordinary collection of European paintings collected by the Putnam sisters date back to 1951. Amy and Anne Putnam, with guidance from their attorney, Walter Ames, quietly began exploring the idea that year, relying on the advice of leading museum professionals as they patiently moved their project forward. During the time that the Putnams were actively acquiring major works of art for the benefit of the public, and lending their pictures to other prestigious museums. they imagined a new, permanent home for their display in San Diego. By the early 1960s, these plans had evolved significantly for a stand-alone building adjacent to the San Diego Museum of Art, where the sisters had started their philanthropic art donations back in the 1930s. SDMA had been designed by a Beaux-Arts trained architect, William Templeton Johnson (1877-1957) in 1926, using the Spanish-Renaissance-inspired vocabulary that the Panama-California Exposition had promoted so successfully. Ames determined that the Putnam Foundation’s collection ought to look invitingly different. With essential funding from another prosperous client with San Diego connections, the Timken Family, Ames set out to identify an architect capable of building a new, state-of-the-art structure to house the priceless artworks stewarded by the Putnam Foundation.

Ames ultimately engaged Frank L. Hope & Associates (later the Hope Consulting Group), a local architectural firm. Frank Lewis Hope, Jr. (1901-1994) came to San Diego as a teenager. It seems likely that he witnessed the architectural transformation then taking place in the city’s Balboa Park. It is hard to imagine that the appearance of Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue’s (1869-1924) landmark California Building (today’s Museum of Us), did not partly inspire Hope’s ambition to become an architect of note. He worked briefly on domestic buildings with legendary figures such as Richard Smith Requa (1881-1941) and Lillian Jeannette Rice (1889-1938) before opening his own firm in 1928. During the 1960s, Frank L. Hope & Associates enjoyed a bustling practice that included numerous important civic structures, including San Diego Stadium (later Jack Murphy/Qualcomm/SDCCU Stadium, recently demolished). Perhaps for this reason, Hope charged one of his younger associates, John R. Mock (b. 1934) with key design responsibilities for the Timken Gallery commission. Walter Ames, deeply engaged in the project on behalf of his clients, provided significant financial and aesthetic oversight.

When it opened to the community in October 1965, the building that Mock designed with Ames’s approval looked strikingly different than the reigning revivalist architecture in Balboa Park. According to some with direct knowledge of the construction costs, the Timken Gallery was then the most expensive building per square foot ever built in the city. Not everyone was an immediate fan of the white travertine and glass structure. Nevertheless, the Director of the National Gallery of Art at the time, John Walker, praised it unreservedly as “a jewel box for the arts.” Today, mid-century modernism has wide currency as a retro style, in addition to ardent fans in the architectural community. The Timken is often compared with iconic museums that were finished soon after it: Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth (1972), I.M. Pei’s Herbert F. Johnson Museum at Cornell (1973), or Gordon Bunshaft’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (1974). San Diego is fortunate to have this remarkably prescient example of modernist principles--pure geometries and undisguised use of materials--within its overall ecology of fine museum buildings. When the museum re-opens later this year, Mock’s sense of clarity and gracious public space will again be on full display, enhancing appreciation of the art that we all miss so much.

Work of the Week #51

Rembrandt van Rijn, Saint Bartholomew, 1657

Ever since the Putnam Foundation acquired a major work by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), in 1952, stewards of the 17th-century masterpiece have been keenly aware of how people from across the globe flock to it. Without overdramatizing, St. Bartholomew serves as a pilgrimage destination for devotees of the artist. The large image is, after all, the only authentic oil painting by Rembrandt in San Diego, and one of just 14 paintings by him in Southern California according to the scholars who know these things (https://mk0rembrandtins14vr1.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Rembrandt-In-Southern-California-Exhibition-Guide-v7.pdf. ) Although the Timken has been closed to the public for almost a year now, the museum has felt a responsibility to ensure that museum visitors have access to Saint Bartholomew, whenever it is possible. To this end, several months ago, we worked with our colleagues at the San Diego Museum of Art to install the painting in their European galleries while the Timken took advantage of its closure to perform some facility improvements. The pandemic vexed even that effort to share. For my part, I’ve postponed writing about this image in this space for almost a year, anticipating the chance to use my “Work of the Week” forum to celebrate Saint Bartholomew’s reinstallation in our galleries.

We don’t know precisely when that will happen, but an end is in sight. Public health guidelines permitting, the museum will likely reopen--magnificently refreshed--later this year. Rembrandt’s painting calls us back from any despondency about delays, however. At his best, as he was when painting St. Bartholomew, the artist was masterful at representing complex states of mind. Leaning forward in a slightly inquisitive manner, the bearded figure in this dark composition seems to ask: “What makes you think you’ve got it bad?” As if in response to his own question, he holds in his right hand a broad, steel blade that references his own martyrdom: Bartholomew was skinned alive. Pointedly (no pun intended), the knife itself reflects an exterior light source, glinting near the image’s center. It is a curious fact about this work that, at one point in its history, a squeamish owner eliminated the knife by having a book painted over it. Thankfully, conservators were able to remove that overpainting without leaving a trace. We should remember that images like this one had precise, didactic purposes. Beyond showing off the artist’s bravura brushwork and his uncanny ability to conjure realist effects, St. Bartholomew’s expressive impact depends on our appreciation of the Saint’s refusal to give in to, or even register personal despair. He remains stoic and utterly convinced of his role in spreading the gospel throughout the world. If we feel disillusioned about the state of things today, just consider St. Bartholomew. Rembrandt puts him on the edge of his seat, poised to spring into action, and visibly unconcerned about whatever fate brings his way. By way of contrast, let’s consider a slightly earlier treatment of the Saint’s iconography, by Jusepe de Ribera (c. 1591-1652) (https://www.museunacional.cat/en/colleccio/martyrdom-saint-bartholomew/josep-de-ribera-o-jusepe-de-ribera-dit-lo-spagnoletto/024162-000 ). In that dramatic, Spanish work, Bartholomew is shown near the beginning of his torment. His physical suffering is palpable as, upside-down, he gazes imploringly back at the spectator. Eschewing the principle of calling for empathy with the martyr, Rembrandt instead offers the firmly seated figure as a source of almost professorial wisdom. Bartholomew’s furrowed brow suggests that he is thoughtfully engaged with the present. Even though he recognizes things aren’t going well for him, he won’t be thwarted from his higher purpose. Let’s take courage from Rembrandt’s example. Emerging from darkness, there is reason to remain hopeful and alert.

Work of the Week #50

Ella Ferris Pell, Salomé, 1890

Ella Ferris Pell (1846-1922) rose to a prominent place in American art circles during the decades immediately following the Civil War. First, she studied with the English-born artist, William Rimmer (1816-1879), at Cooper Union School of Design in New York. While still a student, Pell was praised for her sculpture entitled Andromeda that was displayed in a survey of new talent. Accompanied by her sister and brother-in-law, Pell next voyaged throughout Europe and North Africa from September 1872 until November 1878. That trip is documented by a stack of sketchbooks that are today kept at Vassar College. Upon returning to New York, Pell expanded her career as painter and illustrator. Her triumphs in local exhibitions and the leadership roles she played in several New York art groups meant that Pell’s name appeared often in American art journals and newspapers, including the society pages that tracked her summer forays to resorts in the Catskills. At age 43, Pell returned to Europe, determined to get noticed in the thriving expatriate American art community in France. She entered the atelier of Jean-Paul Laurens (1838-1921), among others, where she was steeped in the exotic historicism of late-19th-century academic painting. Pell had success showing numerous works at the Salons of 1889 and 1890, then returned to New York City. Her career continued to bloom for another decade with allegorical subjects being acquired by major museums throughout the United States. In 1905, Pell moved to the small town of Beacon and spent the rest of her life in the Hudson River Valley. There she worked, not quite in obscurity, but without the substantial, visible triumphs that attended her early career.

Salomé was one of two large paintings by Pell displayed at the 1890 Salon. Among the limited number of American works that the jury selected in May of that year, Pell’s depiction of the biblical femme fatale attracted favorable attention. Instead of focusing on the brazen dance of a bejeweled temptress, as Gustave Moreau (1826-1898) had in his Salon entry of 1876 (https://hammer.ucla.edu/collections/armand-hammer-collection), or the adolescent’s legendary blood lust, as so many contemporaries did, Pell represents Salomé as an introspective figure. The embossed, silver platter that will soon receive her reward for pleasing King Herod, the severed head of John the Baptist, rests casually on her striped skirt. Pell gives her anti-heroine an inscrutable expression and an almost ambivalent attitude, attributes that stoked critical debates at the time, and which have earned this painting extensive scholarly attention ever since. Pell herself recognized the stir that this image caused and considered it to be one of her best. After its public exhibition in Paris, Salomé went on display at the National Academy of Design in New York and, subsequently, went on a tour of the United States. It was purchased by the Boston Art Club for its permanent collection in 1896. Pell’s masterwork has been included in numerous exhibitions throughout the world since.

Some of you may recall that Salomé was a centerpiece of the Captivating Women exhibition held at the museum just before the pandemic brought our in-person programs to an abrupt end. Then, as in the past, Pell’s enigmatic picture was a popular favorite with the public.

Work of the Week #49

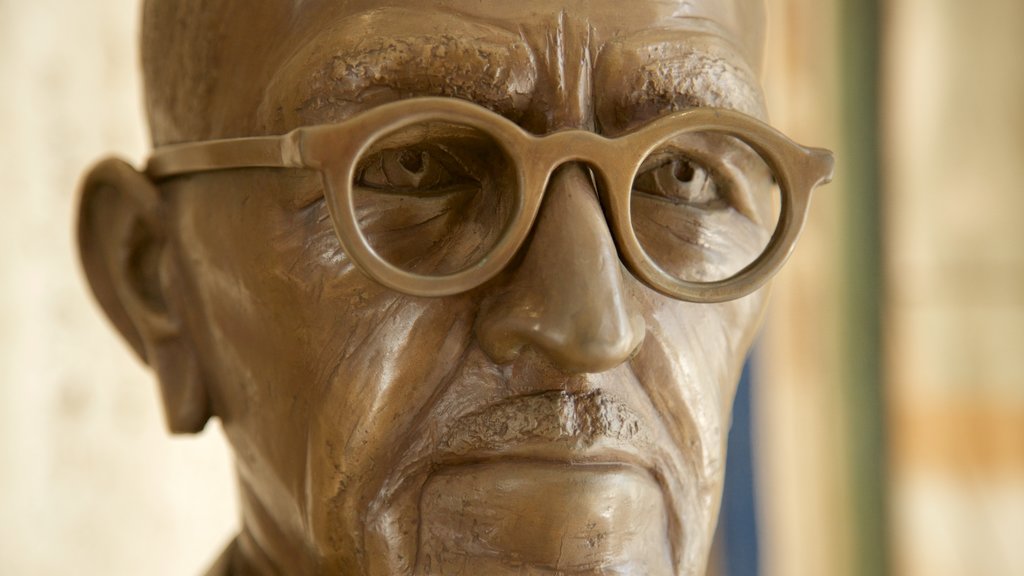

Ruth Hayward, Bust of Walter Ames, c. 1980

When writing about the Timken’s history, it’s practically obligatory to invoke the support of the Putnam sisters--Amy, Anne, and Irene. Less frequently, and usually in passing, I’ve had occasion to mention members of the Ames family, who played another critical role in the creation of this museum. Walter Irving Ames (1894-1980) was the Putnams’ trusted attorney, after all. He orchestrated the sisters’ estate planning in ways that have ensured the long-term health and sustainability of the Timken, even during trying times. Ames was part of the San Diego law firm --Gray, Cary, Ames & Driscoll (later, until 1993, Gray, Cary, Ames & Frye)--which he helped found in 1927. For decades, Ames lived on Hillside Drive in La Jolla, together with wife Marguerite and his children, Nancy and Bob. Highly respected in San Diego business circles, he was sometimes identified as a member of the “Broadway Barons”--a group of downtown leaders that included the likes of Roscoe Hazard and Walter Trepte. At the time of Amy Putnam’s death, in 1958, Ames stepped in to become the President of the Putnam Foundation, the legal entity tasked with purchasing important works of art for a future “gallery” in Balboa Park. Though Ames never pretended to be anything other than a lawyer, he capably negotiated the acquisition of numerous paintings for the museum while simultaneously overseeing construction of the modernist structure that opened to the public as the Timken Gallery of Art, in 1965. Next, he dedicated himself to leading the gallery, serving as its first Director, until 1977, when Nancy Ames Petersen, his daughter, succeeded him in that role. Fellow-board members so appreciated Ames’s dedicated service that they commissioned a commemorative portrait shortly after his passing.

The decision to select Ruth Hayward (b. 1934) as the artist responsible for that lasting tribute may seem like a foregone conclusion. Hayward created the larger-than-life bronze statues of Kate Sessions, Alonzo Horton, and George Marston that greet most visitors to Balboa Park on either side of the Fifth Avenue entrance. She also created likenesses of philanthropists, such as Ellen Browning Scripps, the opera conductor, Karen Keltner, entrepreneur, Dr. Terry Straeter, and the comedian, Lily Tomlin, for prominent public displays. Hayward, a native San Diegan who is now 86, is also a noted nature photographer. Despite her status as a go-to sculptor for the civic leaders, Hayward came to that profession late in her career. Her early background was not in the arts. Hayward trained as a mathematician and worked as an engineer at General Dynamics for four decades before retirement provided her with the opportunity to pursue a second career as a sculptor. Hayward studied with the Leucadia-based artist, T. J. Dixon (?-2018) who with her husband, James Nelson, specialized in similarly realist monuments of noteworthy Californians. The likeness she produced of Walter Ames has stood for more than 3 decades on a pedestal near the entrance to the Timken Museum of Art.

For many years Hayward’s bust was the only permanently, if inconspicuously, displayed work by a woman artist in the building. That is about to change. Stay tuned.

This photo was taken from Timken Museum of Art's Spring 2019 Exhibition Metonymies from the Sonnabend Collection. Bust of Walter Ames sits next to Bob Hope by Jeff Koons.

Work of the Week #48

Luca di Tommè, Trinity with Crucifixion Triptych, c. 1355

Luca di Tommè (active 1355-1389) was a prolific artist who was among the first to join the painters’ guild in Siena shortly after it formed in 1356. Although it is not certain, scholars have suggested that he likely received his own training from Pietro (act. 1306-ca. 1348) and Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1285-ca. 1348), the important family of artists who dominated Sienese painting during the early trecento (1300s). Luca supervised multiple decorations in the Duomo di Siena, a cathedral begun in the 12th century but which was only completed in his lifetime, around 1348. When not managing the crew of apprentices who populated his thriving workshop, he busied himself with commissions to paint book covers and devotional images--both public and private. These were coveted objects throughout the second half of the 14th century.

The Timken’s small triptych was almost certainly created for a private individual’s use. It is noteworthy for the sheer profusion of its biblical narratives. The whole measures roughly 22 inches wide by 22 inches high, when fully opened, but includes no less than seven detailed scenes from the life and death of Christ on its three hinged elements. The central, largest panel represents the Crucifixion. The body of Christ is framed within a blue and white mandorla (almond-shaped orb) where he is supported by the Trinity draped in an encompassing red shroud. Mourning figures, including Mary, Saints John and Francis, appear at the base of the cross while in the top part of this peaked panel, Luca depicts the Resurrection. The triptych’s wings are similarly sub-divided into corresponding iconographies: at top right and left we have the Annunciation; in the center, the Nativity and mocking of Christ; at bottom, the Adoration and the Lamentation. The whole of this heraldic, dialogic, compressed narrative is set off by its bright gold background, at once paying homage to its Byzantine precedents and asserting its conspicuous presence as a luxury object.

A large number of Luca di Tommè’s works exist today. A few ambitious decorations from the late 1360s through 1370 remain in situ, such as the Altar of St. Anne in Siena (c. 1367) or another altarpiece made for the cathedral of Rieti, south of Perugia, which is signed and dated (1370). A spectacular, painted crucifix of roughly the same date that would have been used in liturgical services is now at the Harvard Art Museums (https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/227905?position=0). More commonly, however, we encounter small panels that have been disassembled from much more complex works, likely to make them saleable to collectors long after the Renaissance. For example, a similarly-sized triptych depicting the Virgin and Child with Sts. Louis and Michael (bef. 1362) can today be found at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (https://collections.lacma.org/node/232449). A few larger representations, presumably elements of more ambitious altarpieces, are also attributed to the artist. These include The Assumption of the Virgin (1362) at Yale (https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/263) and St. John the Baptist (late 14th c.), at the Getty (https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/614/luca-di-tomme-saint-john-the-baptist-italian-late-14th-century/). The Timken’s early, complete, and remarkably well-preserved work by Luca is a rare thing, therefore.

Acquired by the Putnam Foundation in 1967, the Trinity with Crucifixion helps distinguish the fine group of trecento works available to study here in Southern California.

Work of the Week #47

After Giambologna, Flying Mercury, late 19th- or early 20th-century

Jean de Boulogne--better known to art history by his nick-name, Giambologna (1529-1608)--was born in Douai, in today’s Northern France, but which was Flanders in the 16th century. He worked for the greatest part of his career in Florence, Italy. It has been suggested that Giambologna’s Medici patrons jealously refused to give him permission to leave the city once he had proven his talents. Indeed, he was widely judged to be the most innovative sculptor among the generation of artists who came of age after Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564). Giambologna’s powerful, intertwined figures in marble and bronze epitomized Mannerist principles as the aesthetic values of his era tipped from pure Renaissance idealization toward heightened Baroque drama.

The Timken has a fine example of Giambologna’s work. Well, sort of. For many years, we displayed a copy of the artist’s Flying Mercury in the museum’s main reception area. An original, sixteenth-century cast of this famous bronze sculpture is now kept at the Bargello in central Florence. Multiple replicas of Mercury are to be found in museums throughout the world. A remarkable, half-sized version is at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, for instance, along with more than a dozen other great examples of this artist’s sculpture which were collected by Habsburg connoisseurs. Some of these casts of Mercury are, if not original, quite old. The Timken’s is relatively new. Experts believe that it was likely created during the second-half of the 19th-century, if not later, and most of the folks we’ve consulted have noted that its resemblance to the expertly-finished bronzes that were produced in Giambologna’s time is strained. A distant relation, a gesture toward the noble past--or maybe just a really nice piece of garden decoration--ours is far from a masterpiece in its own right.

How did this work come to be at the Timken, a place that doesn’t have the habit of displaying replicas in its galleries? There is a good answer to that question in the institution’s archives. Walter Ames, the formidable lawyer who helped San Diego mastermind the construction of the Timken building, was a fan of the National Gallery of Art. During one of Ames’s frequent visits to Washington, D.C. in the early 1960s, he paused to admire the NGA’s cast of Mercury. That version was also created significantly later than the original. It likely dates from the 1780’s/1850’s, but had once belonged to Paul Mellon, whose philanthropy helped boost the creation of that institution. “If good enough for Paul Mellon,” Ames may have reasoned, “then it is good enough for the Timken.” A receipt for Mercury exists still in the curatorial records of the Timken, demonstrating that Ames knew exactly what he was acquiring: a very late copy.

A couple of years ago, we removed Flying Mercury from the prominent, centrally-located space it had occupied since the museum’s opening. This decision, it needs to be said, was reached not because it was inauthentic, but because we desperately wanted to create a more welcoming environment for our visitors. A few ardent fans of the sculpture complained about missing it, but those with whom I spoke directly did not understand that this sculpture was a copy, made long after Giambologna’s time. Indeed, most were surprised to learn it was a modern object, not much older than the modern building in which it had been placed. We are in the process of re-siting Flying Mercury in the small, manicured garden located just to the South of our entry corridor. I am confident it will look lovely there, like the sturdy outdoor garden decoration that it was always intended to be.

Work of the Week #46

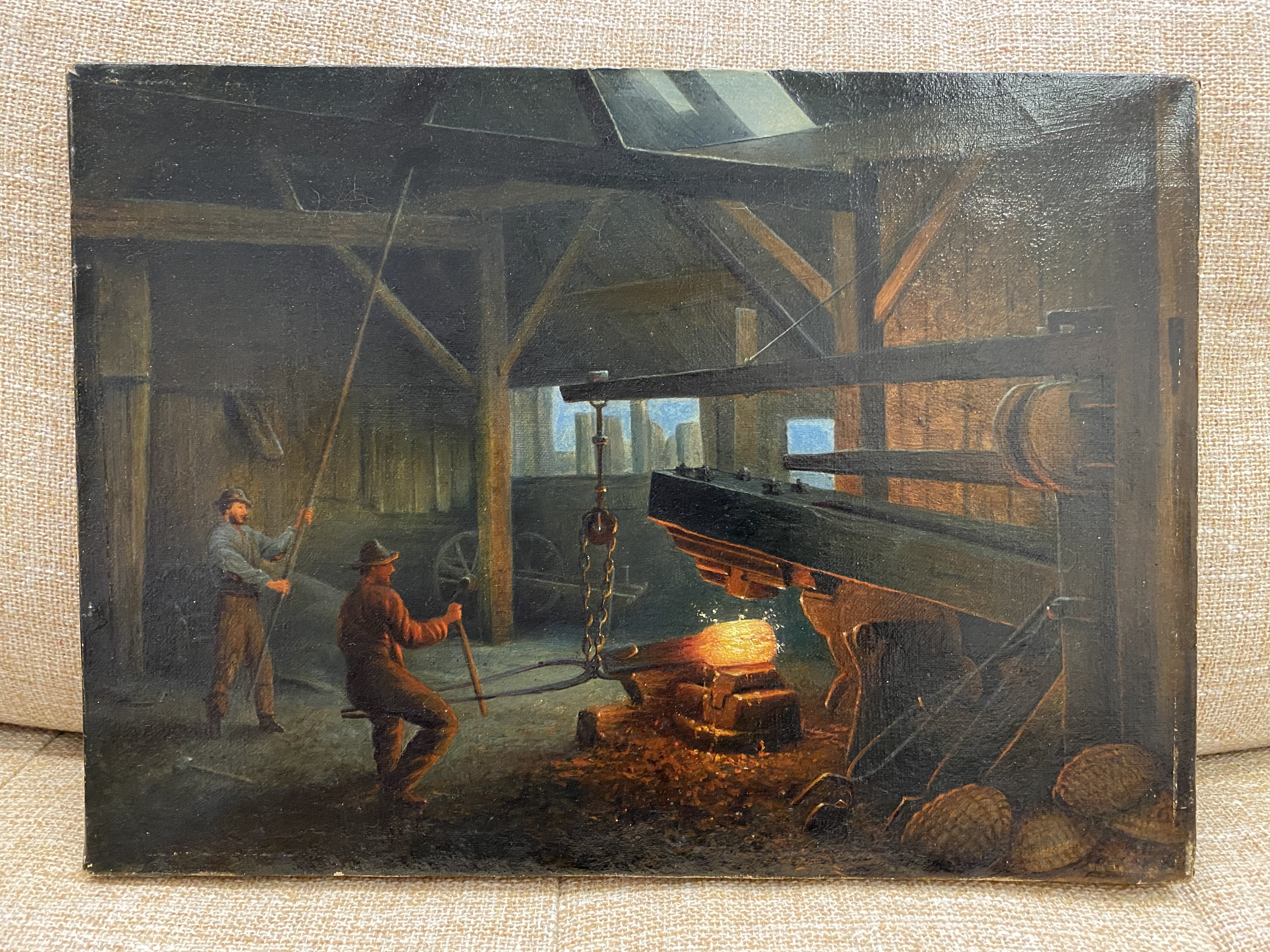

Unknown American Artist, Putnam Forge, after 1870

A small painting--from memory, I’d say it measures only about 8 inches tall by 11 inches wide--hangs on a rack toward the back of a secured storage space at the Timken Museum of Art. Without a frame, it appears inconspicuous, even ignoble. It lacks a signature and, if we turn it over, there are no inscriptions or tags on the back of the canvas to help identify it. The wooden stretcher is crudely joined. The members that form the support were planed by hand and bear only a stencil, also applied crudely, in black paint: “10 8 15”. Apart from this, it is a strangely mute thing. The mysterious object refuses to communicate how it even came to be at the museum.

Let’s turn it over and look at it again from the front. I have studied a lot of pictures, and because my own field is North American art, I am confident that this was painted by an American artist sometime during the second half of the 19th century. The dress of the two men it depicts and the type of large iron forge they manipulate suggests this much. The subject matter is familiar, too. During this period, John Ferguson Wier (1841-1926) painted still more heroic versions of laborers working on forges--one is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and another slightly earlier depiction belongs to the Putnam History Museum in Cold Spring, New York.

The latter reference to Putnam County ought to trigger some recognition for those who know the Timken. The Putnam sisters--Anne, Amy, and Irene--lived in Bennington, Vermont before they moved to San Diego in the early 20th century. Their family’s wealth came from several sources--manufacturing of various kinds, including iron tacks and barbed wire--and meant that they were among both the wealthiest and most philanthropic members of their community. Before the family lived in Vermont, however, they lived in the Adirondacks and ran “the New Russia Forge. . . one of the oldest ironworks in the County, having been erected about the year 1802.” By 1869, the forge was being managed by “Messrs E[lbert] H. and H[enry] A. Putnam,” uncle and father of the Putnam sisters, respectively. The New Russia Forge then “contained four fires and a wooden hammer of about one thousand eight hundred pounds weight” (see Winslow C. Watson, Military and Civil History of the County of Essex, New York, 1869, p. 459).

I think we are looking at that 1800-pound hammer in this small painting. I also think this is the picture that a Putnam relative mentions in a letter sent to Amy and Anne received toward the end of their lives, inquiring whether they still owned the image of the Putnam Forge. It seems possible that they kept it with them in their travels from Vermont to San Diego as a remembrance of their roots in the East. If I am correct, that is how the painting came to be in the vaults of the Timken. Somewhere along the way, it lost its frame along with all the traces of its commemorative function. While I am not necessarily eager to make claims for its aesthetic significance, it is important to the history of the founding of our museum. For that reason alone, I can’t wait to reframe it and share it with you when we all can return to Balboa Park.

Work of the Week #45

Francisco de Zurbarán, St. Francis in Meditation, c. 1635

Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone was born in Assisi, Italy, either in late 1181 or early 1182, the records are unclear. Shortly afterwards, the child was renamed Francesco, or Francis. Part of a prosperous family of merchants, Francis’s parents never particularly encouraged their son’s interest in spiritual endeavors. He ultimately renounced his wealth, however, and went into self-seclusion where various encounters helped sharpen his commitment to Christian faith. Soon after, he founded the religious groups that became pillars of the Franciscan Order: the Friars Minor, in 1210, and the Order of Saint Clare, also known as the Poor Clares, in 1212. Just two years after his death, in 1226, Francis was canonized by Pope Gregory IX.

Representations of St. Francis proliferated immediately after his death and included memorable works by Cimabue (c. 1240-1302) and Giotto (c. 1266-1377) whose stark frescoes recounting his life and miracles enliven the walls of the Basilica of St. Francesco in Assisi--if you haven’t seen them, they should be high on your post-pandemic travel to-do list. By the 1400s, Italian artists had largely codified the iconography by which St. Francis became instantly recognizable in numerous prints, sculpture, and easel paintings. One of the greatest of these is by Giovanni Bellini (1431/36-1516) whose shimmering panel, St. Francis in the Desert (1476-78, Frick Collection) is deservedly considered one of the most important examples of Renaissance art to be found in the United States.

Given this popular context, perhaps we should not be surprised by the fascination that the Spanish Baroque painter Francisco de Zurbarán (1589-1664) demonstrated in his namesake. Zurbarán painted St Francis dozens of times during his lifetime. These works were often made for the Franciscan religious orders who commissioned them as objects of devotion, but some may have also been for private individuals, too. There is an austere consistency with which the Sevillian artist represented the Saint, so fundamentally different from Bellini’s luminous approach of a century-and-a-half earlier. The Spanish artist reveled in the stark simplicity of his subject. Shown alone, deep in prayer or meditation, Francis frequently appears as a presence nearly lost among the shadows. Depicted wearing the dark robes of his order, he either looks up ecstatically toward heaven as he does in a work like St. Francis in Meditation (1635-29, National Gallery of London) or gazing downward with intensity, as he does in St. Francis Contemplating a Skull (c. 1635, St. Louis Art Museum) and in the Timken’s painting by the artist. Especially after 1634, when Zurbarán joined his rival Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) in Madrid, his busy studio churned out copies of these works for an eager market of the faithful.

The most recent acquisition to the Timken’s stellar collection, St. Francis in Meditation was acquired in 2015. There is a similar version of this work at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, also worth a visit soon.

Work of the Week #44

Unknown artist, Still Life, early 17th century

In what seems a lifetime ago, but really was only two years, I spent a careless morning strolling through London. I recall glancing into a gallery between St. James Square and Piccadilly--one of many on a street full of vendors of reputable old master paintings--when I was struck with an odd sense of recognition. Centered in its display window was a small floral still life in an elaborate gilt frame. The work was identified as being by Bartolomeo Ligozzi (1630-1695), an Italian painter of no remarkable importance, except that he was highly regarded throughout the seventeenth-century for depictions of brightly colored flowers. Often Ligozzi painted these blooms in vases set upon stone slabs, but in otherwise shallow, dark pictorial spaces. I stood in front of the window for what must have been a while studying the work. I took a picture with my cell phone. I committed the name of the artist to memory and thought to myself that I needed to do some follow-up research. I went to a meeting and promptly forgot about the encounter.

Sometime after I returned to my work in San Diego, I showed the cellphone image taken in London to an intern who was then assisting the Timken with organization of our curatorial files. The image was too full of reflections on the plate glass to convince her of what I had been thinking: “could this work be by the same artist who created the still life of flowers in a bottle at our museum?” Many attributions have been offered for that picture since it arrived at the museum in 1971. At first, some scholars hoped that it might be by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610), or, more likely, by one of his followers, such as Guido Cagnacci (1601-1663). Why not Ligozzi, then? Sometimes settling questions about attribution is best done through the process of elimination. If we have no clear idea who was responsible for making a particular image--and in this case, we really didn’t--it is nonetheless helpful to rule out the names of artists who could not have done it.

In spite of the fact that we no longer know who made it, the Timken’s still life is painted with an indisputably charming naivete. Like the painting I studied from the sidewalk in London, it is lit from the left side. Stems of red and white carnations erupt in all directions from a low-necked glass wine bottle whose protective raffia covering is in the process of unraveling in a loose spiral. Our painting also includes depictions of several butterflies, a grasshopper, and a spotted lizard sprawled lengthwise across the grey shelf that supports the whole ensemble. That lizard cranes its neck up toward the bouquet above it, testifying to the artist’s skills at creating convincing, illusionistic detail. Depictions of insects and reptiles are staples of baroque still life practice, especially in Northern Europe. That iconography appears slightly less often in Italian work of the same moment, but it is not unheard of there, either. Comparisons between the Timken picture have been made to other early 17th-century works--for example the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston’s Poppies in a Wine Flask (https://collections.mfa.org/objects/33397/poppies-in-a-wine-flask?ctx=eff4655e-2825-4f86-b9f3-7b8c4e363898&idx=0) which shows similarly disordered bunches flowers and torn coils of raffia, but has no critters to speak of. At one time in its past, Boston’s painting was once attributed to Caravaggio. Today the artist is listed as unknown, although one scholar recently suggested Tommaso Salini (c. 1575-1625) as a possible maker.

I haven’t given up on our little painting, or the possibility of someday learning the name of its maker. If not Ligozzi (or Salini), then who? Careful analysis and comparison--the process of elimination at work--might clinch an identification. Or, this might happen by chance--something glimpsed while passing on the street, or on the wall of a museum, might lead to revelation. In any case, let’s just hope that the process doesn’t take another 50 years.

Thomas Birch, An American Ship in Distress, 1841

A truism of art history has it that any painted ship is also always a representation of the “ship of state.” For the British-born artist, Thomas Birch (1779-1851), that seems to have been a durable trope, one that served him throughout a successful career as a maritime painter. His father, William Russell Birch (1755-1834) was also an artist. Together, they set up shop in Philadelphia where they specialized in making engraved views of the city shortly after moving to the United States, in 1794. By the early 1800s, Thomas Birch began working independently of the family business and earned a modest reputation for the topographical landscapes he created of the Pennsylvania countryside. He is said to have painted at least 500 images throughout his career, the majority of them seascapes. Particularly after taking a trip up the Delaware River, in 1805, Birch became enamored of maritime subject matter which he imbued with an experienced sailor’s sense of accuracy. Eventually, he was considered to be a premier “portraitist” of American naval vessels, and battles, during the early 19th century.

While shipwrecks have fascinated Western artists since the Renaissance, Birch seems to have been mostly inspired by Baroque approaches to this sub-genre. Compositions like his Loss of the Schooner ‘John S. Spence’ of Norfolk Virginia, 1833 (LACMA) and the Timken’s American Ship in Distress, painted almost a decade later, are reminiscent of the dramatic and often large-scale images produced during the so-called Golden Age of Dutch painting by the likes of Simon de Vlieger (1601-1653) Ludolf Backhuysen (1631-1708), and Willem van de Velde (1633-1707). Birch balanced his depictions of heroic seamanship with careful attention to the rigging of sails and close observation of weather conditions to create a modern maritime idiom that appealed to collectors in the United States.

The War of 1812, which was itself triggered by disputes over maritime rights, was a source of inspiration for many American artists. Britain had been, up until that time, the greatest naval power in the world, but the United States’ much smaller Armada proved to be a worthy adversary to the much larger and better-equipped British fleet. For Birch, who was born in the Midlands of England, the topic of naval warfare between his home and adopted countries must have sparked conflicted feelings. A big canvas like American Ship in Distress remains vague about its maker’s commitments, except that the work is about being in a state of distress. The picture shows a vessel which has sustained significant damage to its main mast and, adrift in turbulent waters, is in the process of being abandoned by its crew. It is impossible to identify the ship with certainty--the name is effaced--but a depiction of George Washington and a flag on its stern serve to clinch its probable identity as an American warship. Michael Quick has argued that the distant coastline resembles England and that the boats that come to its rescue are likely British, too. If so, Birch might be assumed to give patriotic preference to his British roots in this invented image of risk on the open water.

An American Ship in Distress was acquired by the Putnam Foundation in 1973. Except for the scholarly entries written in the Timken’s 1983 and 1996 collection catalogues, surprisingly little research has been published about the painting. Birch’s picture counts among several noteworthy seascapes in the permanent collection--Fitz Henry Lane’s Castine Harbor and Town, 1851 (see Work of the Week #10) and Claude-Joseph Vernet’s A Seaport at Sunset, 1749 (Work of the Week #36) both hang nearby. These views of ships and harbors provide us with insights into the concerns of maritime painters over a period that stretched from the 1740s to the 1850s and the complex political claims of their time.

Work of the Week #42

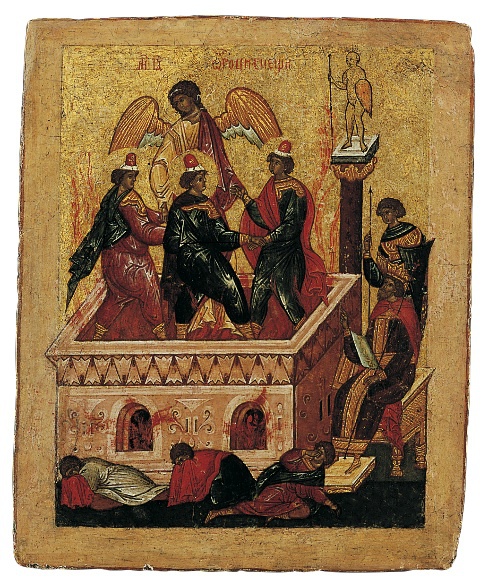

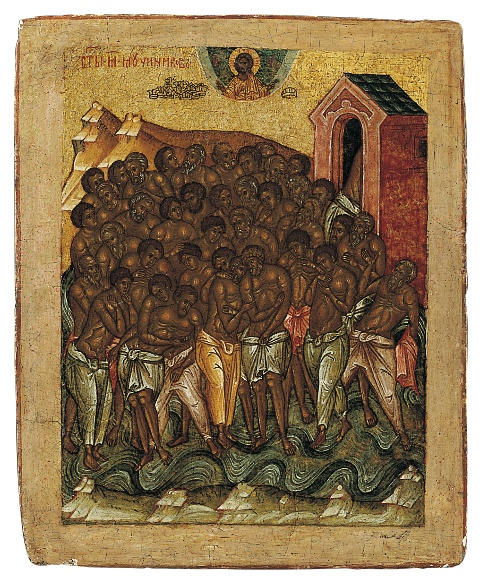

Moscow School, The Georgian Mother of God, Second half of the 17th century

The Timken’s Russian icons tend to be small, a reflection of their still recent private devotional purpose within the Putnams’ family home. Amy Putnam (1874-1958) acquired one unusually large image, The Georgian Mother of God, shortly before the end of her life, at a time when the work’s ultimate destination within a museum must have already figured in her imagination. In 1969, when the first significant catalogue of the Timken’s holdings was published, small mention, and an exception, was made for the display of Amy Putnam’s beloved Russian works. “In only one gallery is there color on the walls,” Agnes Mongan wrote. “That is the gallery which contains a remarkable collection of icons.” Mongan, who mostly advised the museum on its French acquisitions, explained: “It is the one that will be catalogued later. The golden backgrounds of the icons glow against a soft-green cut-and-uncut Italian velvet woven specially for the gallery in Florence.”

Those of us who enjoy the Russian icon gallery at the Timken know that it recently underwent substantial renovation. Wendy Salmond, a scholar of Russian art who teaches at Chapman University, was invited to reinstall the icons in 2017. In that way, Salmond partly fulfilled Mongan’s prediction. The 2017 display included additional works that had long been in storage and introduced new, thematic groupings to the space. In Salmond’s interpretation of the works depicting the iconography of the Virgin with the infant Jesus, including The Georgian Mother of God, she explained that “Icons of Mary . . . were among the first holy images brought to Kiev from Constantinople,” and that “the most important of these were the Hodigitria (“she who shows the way”) in which Mary points to her child as the way of Salvation, and the Tenderness icon, expressing maternal love.”

The Byzantine roots of Orthodox Russian art are clearly expressed in this large panel. The stylized, angular bodies and patterned, striated draperies are reflections of the essential differences that separate the world we live in from the divine realm represented through these expressly religious works. The fact that we do not know the name of the artist who made this big, impressive image is also telling: the maker is insignificant in comparison to the subject matter, which is awesome and holy. As a demonstration of the Hodigitria--Mary showing us the way--The Georgian Mother of God is an especially compelling example. At the same time, this complex painting still captures the sweet emotional bond between mother and child that surely appealed to Amy Putnam, and to tens of thousands of visitors to the Timken each year.

Work the of Week#41

George Inness, Ariccia, 1874

George Inness (1825-1894) was born along the Hudson River, just below Poughkeepsie, but was raised in Newark, New Jersey. Despite his proximity to New York, Inness received hardly any formal training as a painter. Instead, he was hired as an engraver of popular reproductions by Nathaniel Currier (1813-1888), whose partnership with James Merritt Ives (1824-1895) resulted in one of the most prolific print publishing businesses in American history. Working for Currier and Ives, the young artist copied contemporary and historic works by notable European masters and, consequently, learned much about their techniques and strategies for composition. By the early 1840s, Inness started showing his own paintings in exhibitions and received positive critical responses to these works. Landscapes, like Lackawanna Valley, 1855 (National Gallery of Art, Washington), demonstrated the artist’s confidence in his oil painting skills, his subtle attention to topographical detail, and his deep, spiritual identification with American subject matter.

In addition to his explorations of American scenery, Inness traveled abroad repeatedly during his lifetime. He first went to Europe in 1851 and spent most of that trip in Italy, studying Renaissance artists in Florence and Rome. He crossed the Atlantic again, in 1853, stopping that time for extended stays in Holland and England. Upon returning to the United States, he moved his painting studio to Medfield, Massachusetts. A fierce advocate for the abolition of slavery, Inness was unable to serve in the Union Army because he suffered from epilepsy. Instead, he taught art classes to cadets at the Eagleswood Military Academy. Shortly after the Civil War, Inness moved his family to Europe and spent almost four years living there, working extensively in Italy. Ariccia was painted during this third sojourn.

The Timken’s painting presents a view of a town located on the southern outskirts of Rome. Sunset is fast approaching the Alban Hills. Ariccia, thought to be one of the oldest communities in the so-called Latin League, the ancient confederation of communities surrounding Rome that helped protect the city from foreign threats, offered artists a charming, and relatively safe, getaway from the city. The so-called “Roman fever,” or malaria, was prevalent in the late-19th century and was feared by visitors. The cooler elevations of Ariccia offered a respite from disease during the warmer months. Apart from this, it is easy to see why the physical site captivated Inness. The dome of the Church of Santa Maria dell’ Assunta, c. 1661-64, breaks the horizon just to the right of the picture’s center and its slender cupola is counterbalanced by the sliver of crescent moon at left. That Baroque church was designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) and was only one of the town’s attractions. The bridge in the foreground, known as the Ponte di Ariccia, was a comparatively modern construction. It was built from 1847 to 1854 to facilitate the flow of commerce, and tourism, to the hill town’s center.

The artist’s approach to this subject is notably soft and atmospheric, typical of his finest work from this period. As the American art scholar Irma B. Jaffe points out, Inness’s Italian paintings of the 1870s reflect both his conversion to Swedenborgianism, a neo-Christian sect which he adopted several years before, and his growing interest in “pictorial science.” The painter strove to flatten space and to treat it more diagrammatically. One sees this in Ariccia in the succession of planar elements--the long bridge in the foreground, the strict alignment of building elevations in the town itself, and the insistent linearity of hills and horizon beyond. This tendency toward abstraction is carried over to details within the composition, too: a herdsman with sheep in the lower left corner is rendered as pure pattern. Inness was not an Impressionist, per se, but Ariccia signals both his attachment to fleeting effects of light as well as his belief in the “science of geometry” and optical realism. This large painting predicts the later, tonalist works where distinctions between foreground and background elements all but vanish in Inness’s oeuvre.

Ariccia was the fourth American painting to enter the Timken Museum of Art. It was acquired in 1972, the very same year as Eastman Johnson’s Cranberry Harvest, Island of Nantucket.

Work of the Week #40

François Boucher, Lovers in a Park, 1758

As followers of this blog know, the Timken is temporarily closed. This is due to health concerns related to the pandemic. During this time, we have opted to undertake some critical improvements to our facility. When our museum re-opens to the public in 2021, the visible (and invisible) changes will make all of the forced distance from our collection over the past 40+ weeks seem worthwhile, I predict. About a week ago, however, I was reminded of what is at stake with the objects we steward for the public’s benefit when I encountered the museum’s painting by François Boucher (1703-1770) in storage. The crate that houses this work is enormous. It towered above me like a piece of minimalist sculpture. Outside of its protective container and ornate frame, Boucher’s canvas alone measures roughly 8 feet tall and 6 feet wide. Standing beside the box, I was reminded how this object must travel on its side in order to clear the bronze door jambs at the Timken’s entrance. We are accustomed to thinking about the art of our own time in monumental terms--think of Richard Serra’s rolled steel sculptures or Kara Walker’s theatrical silhouettes-- but in the mid-eighteenth-century, French artists had their own ambitious goals for grabbing attention and making heroic statements with their work.

It happens that Lovers in the Park was already on my mind when I bumped into its crate in storage. At almost the same time, the Timken’s registrar, Katherine Noland, received an inquiry about this picture from a British scholar. The researcher was interested in what we knew about the contents of a nineteenth-century country house that once belonged to the Rothschild family in Buckinghamshire, England. The Rothschilds’ sprawling property, known as Mentmore Towers, was designed by Joseph Paxton, the architect of London’s Crystal Palace, and George Stokes. Descendants of the original owners occupied Mentmore until the 1960s, by which time it had fallen into disrepair (maybe they needed a pandemic to force them into tackling the deferred maintenance), but not before being used to store some of England’s most precious art collections during World War II. The estate was sold in 1978 to The Maharishi Foundation and converted into a meditation/educational center. Subsequent owners tried unsuccessfully to convert the Jacobean-styled mansion into a six-star luxury hotel. Mentmore went back on the real estate market in 2010 with a price tag rumored to be £16 million. The elaborate structure continued to be used as a set for music videos and big budget films, including Batman Begins (2005) where it’s painting-festooned corridors stood in for the fictional haunts of Bruce Wayne.

Would it surprise you to know that Boucher’s picture was once an integral part of this grand country house? Purchased by Baron Mayer Amschel de Rothschild--better known to pals as “Muffy”--in 1851, Lovers in a Park was one of several works that were installed in the so-called “White Drawing Room” at Mentmore. We don’t know why, or for what setting, Boucher painted these works almost a century earlier, but we might presume they once formed an elaborate decorative ensemble in France. This painting and another nearly identically-sized one by Boucher called The Fisherman, 1759 (Hamburger Kunsthalle; https://online-sammlung.hamburger-kunsthalle.de/en/objekt/HK-785/der-angler?term=Boucher&context=default&position=0 ), hung on either side of a grand fireplace in the reception hall immediately to the left of the home’s garden entry. Three tall slender panels--L’Offrande à la Villageoise https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/5694/pastoral-scene-loffrande-%C3%A0-la-villageoise , La Jardinière Endormie https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/5695/pastoral-scene-la-jardini%C3%A8re-endormie , and L’Aimable Pastorale https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/5696/pastoral-scene-laimable-pastorale are all today in Edinburgh and likely hung nearby. Like Lovers in a Park, these works all depict young, happy couples in idyllic settings and remind us of a time when human interaction was a simple, even mindless thing. Scholars believe that they, too, shared walls in Mentmore’s drawing room with our composition and its companion image.

The Rothschilds’ descendant, Albert Edward Harry Meyer Archibald Primrose (not kidding), better known to the world as the 6th Earl of Rosebery, sold Mentmore’s most valuable contents at auction in 1964. Shortly afterwards, Lovers in the Park resurfaced in the London art market. The Putnam Foundation purchased the painting, in 1965, on the advice of Agnes and Elizabeth Mongan, two art historians who frequently advised the Timken’s board on collection matters. Boucher’s painting has scarcely left the building since. We should remember that despite its depiction of carefree idleness, it was once, and has been again lately, a picture on the move. While Boucher’s work will eventually make it back into the Timken’s French gallery, not without difficulty, it can’t be rehung there soon enough for me.

Work of the Week #39

Niccolò di Buonaccorso, Madonna and Child, 1387

Acquired by the Putnam Foundation in 1998, Madonna and Child Enthroned is an imposing image. It needed to be. Originally it formed the central element in a highly elaborate altarpiece. Toward the end of the trecento (fourteenth century) the whole ensemble would have been found in the church of Santa Margherita, in Costalpino, on Siena’s periphery. Art historians are not certain exactly when, or why, the altarpiece was disassembled. In 1922, an Italian scholar named Ettore Romagnoli identified the panel, along with two others, and suggested they were likely painted by the same confident hand: Niccolò di Buonaccorso’s. Romangnoli argued that together these fragments once comprised the polyptych commissioned by the parish in Costalpino for a building that appears no longer to exist.

A depiction of St. Lawrence with Patrons also by Niccolò is now held by the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena. That tall vertical panel almost certainly formed another element in the polyptych that was organized around our Madonna and Child. It would have appeared to the right of our image. Yet another similarly-sized painting of St. Paul is today in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It could have belonged to this ensemble, too. Nothing is simple, however. The St. Lawrence in Siena at some point in its past was extensively repainted, and someone moved it to a nearby church, Sant’Andrea a Montecchio. This might have happened as early as the sixteenth century. Archival photographs at the Frick Collection show both the original and overpainted versions of the panel, enabling us to witness St. Lawrence’s transformation into St. Margaret. The elaborate, cinquefoil architectural framework that we know so well from the Timken display, remained perfectly intact all the while (https://www.frick.org/blogs/photoarchive/st_lawrence_recovered).

Niccolò di Buonaccorso (c. 1348-1388) was one of many sophisticated painters to emerge from Sienese culture in the late 1300s. Afterwards, he was judged a minor artist by some scholars of Renaissance painting. Why? In addition to this extraordinary example of his practice, we have another work of Niccolò’s at the Timken, the so-called Virgin of Humility (c. 1370-75, see Work of the Week #16). That little triptych underscores just how polyvalent this artist was. Both works include demonstrations of the artist’s investment in symbolism--the single white rose that Christ delivers to his mother’s elongated fingers is a sign of her purity--as well as ordinary reality--the sewing basket in the little triptych was meant to convey Mary’s mundane preoccupations. The presence of both large and small, public and private devotional images, each managed with nuance and control, shatters any presumption that this artist was somehow limited to producing just one kind of work.

The Timken mounted a small show of religious works produced in Niccolò’s orbit, back in 1998. Called Art and Devotion in Siena after 1350, the exhibition was curated by Pia Palladino. Palladino makes a strong case for the importance of San Diego’s triptych and altarpieces. Further research needs to be done, but connecting the group of smaller panels already attributed to the artist, a list that includes the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s The Lamentation of the Dead Christ (c. 1380-88), The National Gallery of London’s Marriage of the Virgin (c. 1380), and the Uffizi’s Presentation of the Virgin at the Temple (c. 1380), might someday help associate them with other, contemporaneous polyptychs. Such panels may have comprised parts of a single altarpiece’s predella, or base, or else they formed independent sacred works. These circumstances are also worth exploring even as we contemplate the lasting, satisfying immediacy of a work of art painted more than 630 years ago.

Work of the Week#38

Jasper Francis Cropsey, Apple Blossoms, 1887

Landscapes make complex statements about the places they depict. In the Timken’s American gallery, the depictions are by the major contributors to this genre: George Inness (1825-1894), Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902), Thomas Moran (1837-1926), and Jasper Francis Cropsey (1823-1900). Together with Thomas Cole (1801-1948), Asher B. Durand (1796-1886), and Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900), these artists suggested the principal directions for landscape practice in the United States that were closely followed by later practitioners. Cole and Church may have led the way in venturing up the Hudson River Valley to paint its relatively unspoiled vistas, but they were quickly followed by the likes of Cropsey and others.

The so-called Hudson River School painters are best known for their large-scale, dramatic depictions of conspicuously American scenery: Niagara Falls, the Rocky Mountains, and Yosemite, among other sites beyond the Catskills. These intrepid artists’ decision to record--oftentimes hyperbolically--the natural wonders of the United States became synonymous with elevated ideas about divinely ordained beauty as well as national doctrines of westward expansion and colonization. Painters like Bierstadt and Moran traveled West and, indeed, did not stop until they reached the Pacific Coast. Cropsey traveled to Europe on a couple of occasions--the first time was in 1847 when he took over Thomas Cole’s studio in Rome--but he seems only to have traveled as far West as Wyoming on the North American continent. The artist’s mature work reflects his taste for vistas informed by European attitudes toward the sublime, albeit matched to the settled splendor of the Mid-Atlantic region.

Cropsey was raised in a devoutly Christian family on a farm on Staten Island. He pursued an architectural career before committing himself fully to painting. In 1843, at age 21, Cropsey became the youngest member to be named an Associate of the National Academy of Design, achieving renown both as an exhibiting artist and as a teacher. His detailed observations and theatrical compositions earned him comparisons to contemporaries in England, such as the Pre-Raphaelites. This identification is not very surprising. Cropsey and his wife, the artist Maria Cooley (1828-1906), lived in London from roughly 1856 to 1863 where they befriended John Ruskin and others associated with that ultra-realist movement. Even while living abroad, however, he continued to paint subjects based in his memories of the American countryside. Large paintings like Autumn--On the Hudson River, 1861 (National Gallery of Art) were exhibited in England to much critical acclaim.

Later in life, having attained significant commercial and personal success, Cropsey opted to paint in a less obviously theatrical style. Sketches like the Timken’s Apple Blossoms belong to this moment in the artist’s long career. Our small picture shows the landscape near Cropsey’s home in Hastings-on-Hudson. The image conjures the glory that springtime offers rural communities without exaggeration or any invented effects. A footpath splits the composition’s verdant foreground in two and leads the spectator’s eye through a rustic apple orchard. Beyond the blossoming trees, a pair of figures can be seen walking together and, further on, we glimpse the Hudson River with its boats and hills beyond. It is a simple, harmonious scene, like many others from this period in the artist’s life, and markedly different from the spiritually-informed emotionality of his best-known works.

Work of the Week #37

Nicolaes Maes, Portrait of a Lady, 1677

Pictures can be puzzles, some more obviously than others.

Think of The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98-1548). Standing before that monumental, nearly square portrait of two young men, we cannot avoid staring quizzically at the conspicuous, strangely elongated, grey form that hovers in the immediate foreground. This puzzling shape is just one of several rebus-like elements that the artist introduced to his large composition. When viewed from a steeply oblique angle, the anamorphic grey form resolves into the depiction of a skull, an emblem that overlays the entire scene with ominous dread. The two prosperous figures that flank the skull--ambassadors from France to the court of Henry VIII--may be surrounded by accumulated signs of knowledge but, like everyone else, they are destined to die. Holbein’s is a satisfying, if dismaying, puzzle to solve. I never visit the National Gallery in London without stopping in front of his masterwork for at least a short while to marvel at its pictorial invention and to ponder its maker’s lasting message about the ends of cultured experience.

The Timken has its own share of puzzling paintings that promise rewards if resolved. One example: I have spent a lot of time wondering about a small picture in our Dutch/Flemish gallery that is presumed to be the work of Nicolaes Maes (1634-1694). Portrait of a Lady was acquired by the Putnam Foundation as a gift, in 1986. The museum counts a few gifts in its permanent collection, but most of the works were purchased either by the Putnam sisters or else by the museum’s leadership in keeping with a strategic vision to bring the best possible representations to San Diego. Maes is a bit of an outlier. He was born in Dordrecht but moved to Amsterdam while still a teenager. Once there, he became a star pupil in the thriving workshop that Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-69) maintained. Maes started his career as a genre painter, producing scenes of everyday life for a burgeoning art market. By the 1670s, he shifted the focus of his practice to painting portraits of wealthy elites. Works such as his Portrait of Petronella Dubois, 1677 (Rijksmuseum), show off Maes’s skill at painting sitters surrounded by sumptuous materials and displaying natural expressions.

Scholars have speculated about the identity of the sitter in the Timken’s portrait, which remains a mystery. A few have argued that it could be a youthful portrait of Mary Stuart II, daughter of the Duke of York (King James II) and Anne Hyde, but without providing much convincing proof. If the date in the lower right corner of the painting is correct, Mary would have been fifteen years old at the time this work was completed. That date would further suggest that this particular portrait was done to commemorate Mary’s marriage to William of Orange, with whom she would eventually rule England, Scotland and Ireland. We know that Maes painted a pair of portraits of William and Mary around the same time (Blanton Museum of Art, Austin) but those depictions differ in that they are both smaller ovals and are bust-length. The Blanton’s Mary doesn’t look very much like the light-haired woman in the Timken’s picture. Ours better resembles a slightly larger work by Maes known as Portrait of a Lady as Diana (art market) which once belonged to the Dutch royal family. Both that picture and the one in San Diego feature the same woman with blonde curls and smiling face.

Puzzling over these resemblances sent me back to our curatorial records. Maes’s painting appeared in two early auctions. The first was held from July 26th to August 16th 1859, at which the entire contents of “Lord Northwick’s Extensive and Magnificent Collection of Ancient and Modern Pictures” were offered to the public in London. Indeed, Baron Northwick (born John Rushout) was a great collector who, among many other works, owned a portrait of the Duke of Orange. But lot #1791 in his estate describes a “Portrait of a Princess of the House of Orange, with a Dog.” The catalogue identifies the artist responsible for this painting as “G. Netscher,” not Maes. Caspar Netscher (1639-1684)--also known as Gaspard Netscher--was Maes’s contemporary who lived in the Hague. Netscher specialized in portraits of well-to-do women placed against dramatic backgrounds, as well. A second record of the Timken’s painting appears almost a half-century later, in 1907. By that time the work belonged to the Massey-Mainwaring Collection, which was dispersed by Messrs. Christie, Manson & Woods “at their great rooms” on St. James Square over a six-day period. The auction catalogue includes a reference to the picture as lot #17. “Portrait of a Princess of the House of Orange,” now attributed definitively to Nicolaes Maes, is described as follows:

Small, three-quarter figure, standing in front; her right arm rests on a table, on which is a small spaniel; a column and red curtain in the right background, landscape on the left. Signed and dated 1677.

This seems to be a match to the picture in San Diego. Annotations in the catalogue margins suggest that the painting sold on March 16, 1907 for £183.15. Its provenance is listed there, too: “From the Northwick Collection.” For me, the failure of both British auction houses to identify the sitter as Mary Stuart is surprising. She was the Queen after all. Could this be another female member of the House of Orange, then? I also wonder under what circumstances did this Portrait of a Princess of the House of Orange, change attribution (and perhaps acquire a signature and date) between 1859 and 1907? Small puzzles, perhaps, but worth pondering if we hope to understand this work’s place in our collection, and in history.

Work of the Week #36

Claude-Joseph Vernet, A Seaport at Sunset, 1749

Even at the end of the day, it is a busy port. Shadows are lengthening and dusk begins to settle, but a variety of figures are spread across a broad stone pier. A landing party has evidently just arrived and family members rush to embrace a young man who disembarks from the small dinghy. Visitors in exotic costume converse and take casual note of the reunion while sailors distract themselves by playing games of chance. A couple of dogs snarl at each other on the steps. In the middle of the bay, a Dutch warship has just fired a shot--a friendly salute--and plumes of orange and grey smoke billow from its stern. What does all of this signify? Why did Claude-Joseph Vernet (1714-1789) paint this particular view?

In all likelihood, this is an invented scene. Cecil Gould, writing for the Timken’s 1996 collection catalogue, suggested that the picture depicts the port of Naples. But Gould points out there is scant topographical evidence to clinch this as a portrait of that Southern Italian city. A Seaport at Sunset was completed in Rome in 1749. In fact, Vernet painted numerous views of Naples during his long, successful career. Many of these were done for wealthy grand tourists who craved dramatic proof of their cultured travels. An entry in Vernet’s notebook written around this time records the commission for a pair of seascapes by Charles-Louis Beauchamp, better known today as the Comte de Merle. The Comte was a French diplomat, as well as a connoisseur of painting and sculpture. The sale of his personal collection in Paris on March 1, 1784 was a noteworthy event and was extremely well documented. One catalogue included a long entry, #22, on a pair of works by Vernet:

Two paintings representing different aspects of Naples from its port; one shows the sun setting and the arrival of a sailor who is announced by a cannon shot; a group disembarks from a launch and is welcomed by men, a woman and child. Numerous figures of different nationalities are scattered throughout the foreground, some sitting, some occupied with transporting merchandise. To the composition’s right, a lighthouse stands at the entry to the canal while in the distance we see the prosperous port itself. On the same half of the composition, one notes the tall mountains that surround Vesuvius. A warm sky tops this magnificent picture with its 46 major figures, made as beautifully and as well arranged as could possibly be desired.

The other painting, also a view of the port of Naples, represents a great body of water. Through the rain, at left, we glimpse a building which appears to be an Admiralty. On the opposite side, on sees a massive rock protruding into the sea itself. Before it, one counts about 20 figures, some busy loading mules and horses with a variety of goods, the others are fishermen preoccupied with their catch. A rainbow, ingeniously placed, floats in an admirably clouded sky. These works were signed in 1739. [Alexandre-Joseph Paillet, Catalogue des Tableaux qui Composent le Cabinet de M. le Comte de Merle, pp. 14-15]

Except for the mis-dating, it seems likely that the Timken’s Vernet is the first of the two works described in this catalogue of Beauchamp’s art. Paillet further observed that the two works had “details drawn so precisely [they] could by their charm of color hold their own next to the finest [by] Claude [Gellée (1604-1682)].” The paintings were sold as a pair in 1784 but they did not remain together. For the better part of two centuries, our canvas by Vernet ended up about a dozen miles outside of Dublin, Ireland, at Luttrellstown Castle, where it was displayed until the 1970s, after which it was purchased by the Putnam Foundation for San Diego. Its partner went through a series of owners in France and ultimately came to be known as L’Arc en ciel: An Italianate Coastal View with a Rainbow, Fishermen and Peasants at an Inlet in the Foreground, a Shipwright’s Yard Beyond. That darker, but identically-sized work re-emerged at auction in New York, not too long ago.

Work of the Week #35

Master of the Magdalen and Unknown Florentine painter/s, Madonna and Child with Two Angels and Twelve Scenes from the Passion, c. 1300

The oldest painting at the Timken Museum of Art is simultaneously one of its most delicate and mysterious. The work I am thinking of is a dossal--an ornamental image that was intended for display behind the altar of a church. Early on, devotional icons like this one were painted on fabric. During the Renaissance, however, they were more likely to be painted on wood panels and were precursors to increasingly elaborate altarpieces whose popularity spread throughout Europe. Scholars believe that this particular dossal was made in Florence. Less certainly, it seems to have been produced for the Augustinian convent of Santa Maria dei Candeli, founded in the early 14th century. That church was significantly enlarged in the 16th century and ceiling frescoes by Niccolo Lapi (1661-1732) and a new altarpiece by Carlo Sacconi (active 1692-1747) were added to it in the early 18th century. In the trecento (i.e., 1300s), however, Santa Maria dei Candeli must have been a small, austere space. If this dossal was present there at the beginning, it would have stood out as a resplendent image within an otherwise spare interior.

We have lost track of the name or, more likely the names, of those responsible for the Timken’s dossal. In an essay published in The Burlington Magazine in 1930, the San Francisco-born art historian George Martin Richter, likened it to known works by Meliore di Jacopo (act. 1239-1284) based on purely stylistic grounds. Richter suggested that the hand that painted this particular dossal belonged to a slightly later moment, however. Subsequent experts have concurred with Richter. The central depiction of Mary holding the infant Jesus in her lap and flanked by angels looks Medieval--flat, stylized, and heraldic in color. Precious stones were originally inlaid in Mary’s crown but these were removed long before the dossal ever came to San Diego, in 1967. Just imagine these jewels glinting near the composition’s middle whenever the dark, horizontal picture was illuminated. Twelve smaller scenes from the Passion surround the Virgin and Child. In contrast to the stiffer, more Medieval treatment of the central group, these images are highly animated and demonstrate their maker’s growing knowledge of perspective. As in the work of leading Florentine artists of the trecento, such as Giotto (1266?-1337), bodies and spaces in these subsidiary rectangles are treated more volumetrically as the artist struggled to represent the world in three dimensions.

How can we make sense of such contrasting approaches within the same work of art? It seems likely that more than one artist could have worked on the Timken’s dossal. This would explain the difference in treatment between the central image of the Virgin and Child and the flanking scenes. It was not unusual for artists to collaborate in this era. They often worked together in allied workshops. Some scholars have speculated that the dossal was begun in the late-13th century by one artist, who presumably died, only to be finished in the early-14th century by another. Anne Derbes, in a 1996 book about Passion iconography in early Italian art, associated the Timken dossal with the names of two little-known artists: the so-called Master of the Magdalen (active 1265-1290) and the Master of San Gaggio (active 1300). Such an explanation rationalizes the divergent pictorial strategies employed in the center and sides of the same work. Careful scientific analysis might suggest firmer answers. For the time being, recognizing this multiple authorship goes a long way toward making sense of the work’s divided appearance.

Further complicating this puzzling situation, our image has been transferred from one support to another. We think this happened in the 18th century and, if so, that would roughly coincide with the renovations that took place at Santa Maria dei Candeli. The effort to preserve the painting--already 400 years old--by mounting it on a fresh wooden panel was accompanied by the appearance of a new inscription: an 18th-century text on the back of the work identified the dossal as a gift of the Capponi family. Francesca Teresa Capponi (1705-1775) was the abbess of the Augustinian convent of Santa Maria dei Candeli. The same inscription attributes the picture to Cimabue (c. 1240-bef. 1302) who, in addition to being Giotto’s teacher, is typically given credit for having inaugurated many pathbreaking pictorial conventions of the Renaissance. Today, no one thinks the inscription is accurate, but it underscores the hopefulness that surrounds this--and so many other--important devotional works of the trecento.

Work of the Week #34

Frans Hals, Portrait of a Man, 1634

What is there to say about an unidentified portrait?

The Timken Museum of Art has only a couple of these in its permanent collection. It is a curatorial mission, or maybe a folly, to work toward firm identifications of such works. Let’s call the unnamed man in our painting by Frans Hals (c. 1581-1666) Mr. X, just for the time being. In addition to his ingratiating demeanor, we know precious few things about him and his seventeenth-century existence. For instance, we know his precise age at the time he was painted: 48. That number appears prominently on the surface of Mr. X’s portrait, at upper right, above the date and Hals’s own initials. He wears the dark costume that was typical of Dutch community leaders, or regents.

We are pretty sure that he was married, too. His wife had her portrait by Hals painted at the same time. She is displayed--also as an “unnamed” sitter--at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Both of these paintings are on identically-sized oak panels (actually, the measurements provided on the DIA’s website suggest that the Timken support is 1/8 of an inch taller). In contrast to Mr. X’s solicitous look, Mrs. X stares contentedly back at the beholder, hands clasped tightly her lap in proper Dutch fashion. She was 14 years younger than her husband when their likenesses were created. Like him, Mrs. X wears an intricate lace collar of a kind that would make Ruth Bader Ginsburg envious. At some point in their past, the couple split into two different directions. It appears that Mr. X was sent off first to an auction in Amsterdam, in 1873, and Mrs. X ended up in a private collection in Cologne, Germany, until 1912, after which she also entered the art market. We can only wonder why they went separate ways: ungrateful heirs would be one guess.

Since we are speculating, we might further surmise that this couple once lived in Haarlem. Although he was born in Antwerp, Frans Hals worked in that town near the North Sea from roughly 1611 until his death. A picture dated 1634, like this one, would have been created right in the middle of the Thirty Years War, not an especially propitious time. Haarlem was still recovering then from the associated economic turndown of the 1620s. By 1634, having been at it for more than two decades, Hals had nonetheless earned a reputation as Haarlem’s leading portraitist and prosperous clients in the region likely sought him out first. He managed a vibrant studio and even counted Judith Leyster (1609-1660) among his many now-famous students. Leyster went on to become the first female member of the Guild of St. Luke in Haarlem, in 1633, chiefly as a result of her time spent training with Hals. It is possible that Leyster helped with the stream of portrait commissions coming into the studio, but scholars believe that Hals kept the best projects for himself, busying his assistants with the production of genre paintings or copies of his most popular works, for example, his “rough manner” depictions of Dutch types such as Malle Babbe (1633, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) or The Merry Drinker (1628-30, Rijksmuseum).

Mr. X is not a type. We gaze upon his face from slightly below and recognize that it depicts a real person. Like another memorable portrait by Hals that long ago lost its personal identification, The Laughing Cavalier (1624, Wallace Collection, London), we sense immediately that this was a particular human being, possessing a sense of humility and certain foibles that may remain unknowable to us, but which endeared him to his friends. Hals’s flair for brushwork enhanced this feeling of affability. I imagine Mr. X approaching Hals in his busy studio and striking a bargain with the artist over the paired portraits he thought would help commemorate his life. There is, perhaps, a notarized paper in an archive somewhere that captures this transaction. When it is located, we will learn Mr. X’s name, perhaps his wife’s identity, the date he commissioned the work, and the amount of money he paid Hals to produce these likenesses in oil paint on heavy oak panel. Everything will be just a little clearer. In the meanwhile, we can marvel at the subtlety of the artist’s method, his skills at conjuring personality with a few swiftly applied daubs of paint. As the art historian E. P. Richardson put it, Hals was in demand for his ability to “catch the revealing momentary gesture--the characteristic glance, smile, or gesture of the hand.” In looking at the Timken’s picture, we can’t help but agree that these were the artist’s enduring strengths.

Work of the Week #33

Thomas Moran, Opus 24: Rome, from the Campagna, Sunset, 1867

Thomas Moran (1837-1926) cared deeply about artistic legacy. His own self-identification with specific works of art was important to him. Late in life, Moran began pressing his thumb into still-wet oil paint to prove that he was the maker of those representations. Another demonstration of this can be seen in the running list the artist kept of his noteworthy efforts. The English-born landscapist referred to this unique record as his “Opus List.” During the mid-1860s, Moran enumerated 42 works as worthy of this designation. He appended to the document detailed notes about these paintings’ ownership, as well as the prices that collectors paid for them. The Opus List is today kept in the Archives of the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma along with more than 200 works by Moran. The manuscript provides an important key to the artist’s private judgments. Occasionally, Moran transcribed “Opus” numbers onto the objects themselves, usually adjacent to his signature, as a means of confirming their significance.

As its formal title and numeric inscription indicates, Opus 24: Rome from the Campagna, Sunset (1867) belongs to this special category within Moran’s broader oeuvre. The picture dates from just after the Civil War, and was the first major work that Moran completed in his Philadelphia studio after returning from the second of his multiple visits to the European continent. This particular sojourn started in Paris and lasted from June 1866 to May 1867. Scholars have shown that Moran passed several weeks in the countryside South of Rome, exulting in the spare beauty of the campagna and studying its traces of ancient civilization before sailing back to the United States via Liverpool. Opus 24: Rome from the Campagna, Sunset is likely based on a highly finished drawing called Rome near the Claudian Aqueduct dated March 6, 1867. That drawing can be found today at the East Hampton Library on Long Island. Like the Timken’s painting it depicts a series of fragmentary aqueducts to the right. These hulking forms lead our eye back to Rome, visible in the distance, just as those structures conveyed water to the city in the historic past. Instead of lizards scrambling over the rocks in the foreground, as we see in the Timken picture, the drawing depicts a solitary figure taking in the vista. If one looks carefully at both the sketch and the painting, the dome of Saint Peter’s Basilica can be glimpsed breaking the horizon line near the works’ compositional centers.