Work of the Week # 6

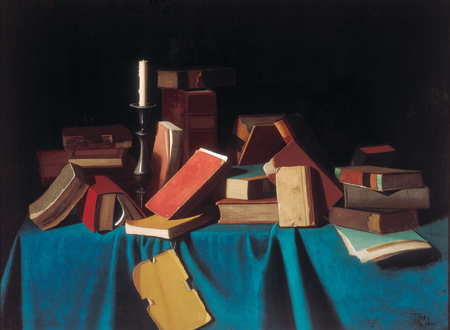

Celebrated as a “jewel box”, the Timken is at once an uncommon collection of unquestioned “gems,” and a blissfully serene place to contemplate lastingly great works of art. A painting like In the Library fits awkwardly within such characterizations, however. An image of clutter, it looks ill-suited to any jewel-box. Chronologically, In the Library is the most contemporary work on the museum’s walls. It bears a date of 1900 (or, perhaps, 1901—it is hard to be sure). It is one of the institution’s most recent acquisitions, having been purchased by the Putnam Foundation in 2000. John Frederick Peto, the artist who created it, while central to the story of still-life painting in the United States, is far from a household name. Peto’s pictures are not likely to be mistaken for Pieter Claesz’s, but his deadpan illusionism has been cited as an inspiration to the likes of Jasper Johns. This large, forward-looking picture occupies a somewhat paradoxical place within the Timken’s founding logic, therefore.

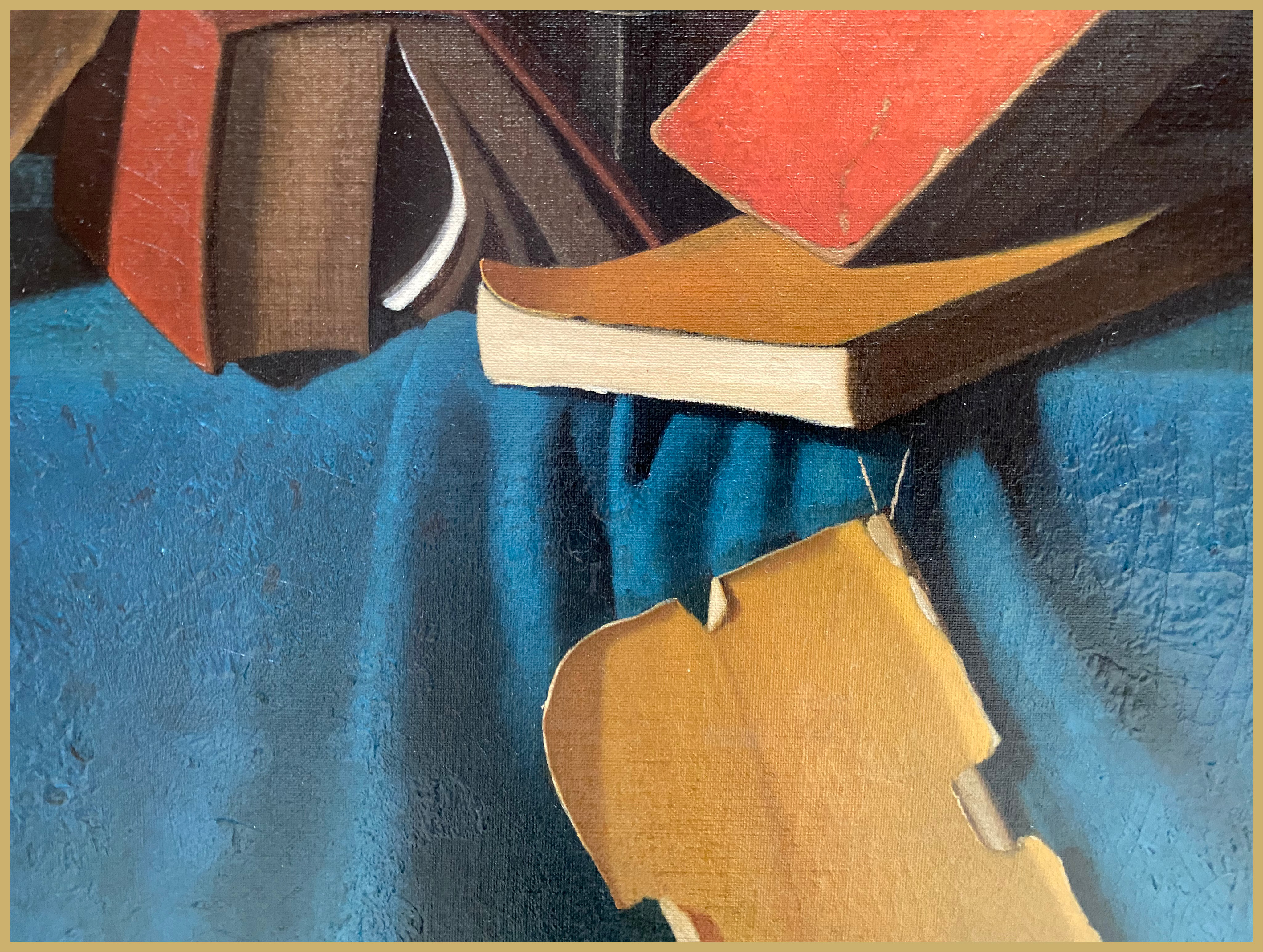

The books that make up In the Library are in poor shape. They pile and tumble across a sky-blue tablecloth, covers chipped, leather bindings blistered, their spines split through careless use. These mute objects—no writing can be deciphered on Peto’s texts—are held in place by what can only be described as a provisional sense of gravity. A sheaf of papers at right projects uncomfortably beyond the table’s limit and an especially tattered cover hangs precariously over the front edge, prevented from falling into our space only by the thinnest triangle of thread. These elements appeal to unseen readers who might thoughtfully re-set them on the tabletop. But no one’s coming and, never mind, there’s hardly room enough to relocate these forlorn objects in the space provided. In the end, we understand they are balanced tentatively across the crowded space, confronting us with their own deliberate sullenness. Peto’s monotonous dark rectangle, comprised of smaller, colorful rectangles, is relieved only by a single, vertical element: an unlit candle that emerges from the furled lip of a pewter holder. That white stripe divides an otherwise featureless horizon. Another source of light, perhaps one less obviously nostalgic, streams in from the left and illuminates the picture’s stripped-down geometry.

Peto was one of several masters of trompe l’oeil—trick-the-eye—painting who emerged from Philadelphia toward the end of the nineteenth century. Decades after the Peale family introduced this popular genre to the region, Peto competed with the likes of William Michael Harnett, John Haberle, Jefferson David Chalfant, and other masters of hyperrealism for critical supremacy. Simulating quotidian things—letter racks, instrument stands, and lots of bookshelves—these painters played with inside jokes and self-reference. Works by Peto and Harnett were so similar as to eventually become confused by later scholars of American art. What was the point? In a brilliant analysis of post-Civil-War representations, Jay Cook argues that trompe l’oeil images, like this one, satisfied a modern craving for credulity. Low-brow magical acts, automata, and the rise of circus sideshows further underscore this tendency. Cook’s book, The Arts of Deception: Fraud in the Age of Barnum (Harvard, 2001) surveys inauthenticity and how it might be interpreted as a broader, modern cultural phenomenon. Peto’s messy library belonged fully to that mindset. It resonates with our own time and introduces a striking difference to the Timken’s orderly rationale.