Work of the Week #11

After Antoine Caron/Faubourg Saint-Marcel Workshop of Marc de Comans and François de la Planche, Stories of Queen Artemisia, c. 1620

It’s been a while, so let’s remember that the Timken’s central space is ringed with heroically-scaled art. Four large tapestries are often overlooked by visitors to the museum who come to see the museum’s renowned paintings collection. In our contemporary moment, we have lost the habit of considering objects like these carefully. Decorative textiles of this kind were once compulsory parts of palatial settings. Their dense fabric helped warm often-chilly interiors and their sumptuously-colored narratives provided much needed visual distraction. Made from precious materials including silk, silver, and gold thread, these intricately designed works occupied a privileged place in European art history from the late Medieval period through, at least, the mid-nineteenth century. Unlike traditional murals, which were fixed permanently to the wall, a tapestry could be rolled up and transported to another location, which made them useful to wealthy property owners but difficult to track over time. Important artists such as Rubens and Boucher participated in their creation. Well-known examples can still be found in major museums throughout the world, including the so-called “Unicorn Tapestries” at the Metropolitan’s Cloisters in New York City, and The Hunts of Maximilian cycle at the Louvre.

The four tapestries that hang in the Timken’s central hall were produced in Paris around 1620. Based on drawings made by Antoine Caron (1521-1599), these were created in the legendary Faubourg Saint-Marcel workshop of Flemish artisans established by Marc de Comans and François de la Planche. The original cycle, of which San Diego has only a part, may have been comprised of as many as twenty separate scenes. The Italian-born Duke of Savoy, Charles Emmanuel I (1562-1630) most likely commissioned the ensemble to commemorate the wedding of his son, Victor Amadeus, to the daughter of Henry IV and Marie de Médici, Christina of France, a first cousin. The consolidation of power that this marriage sought is reflected in the narrative itself. The tapestries tell a popular, apocryphal story of Queen Artemisia, a benevolent ruler who was, in fact, a composite of several historical women. Artemisia’s character was understood in the late 16th century to function as a tribute to Catherine de Médici. The panels at the Timken recount two distinct episodes from the epic poem about Artemisia. One pair illustrates the fundamental goodness of the queen as she takes into account the concerns of her subjects from all ranks of life--The Requests of Citizens and The Petitions--while the other shows her sharing the spoils of conquests fairly--Distributing the Booty and A Group of Soldiers. The Duke must have hoped that his own son would enjoy the ear of the regent and be the recipient of similar demonstrations of generosity as a part of the royal household.

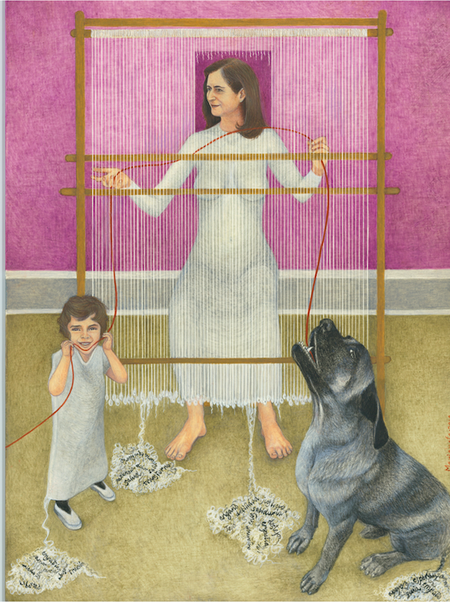

Revisiting these works of art and their messaging about wise, powerful women reminds me how nicely they set the stage for the next curatorial project at the Timken Museum of Art. Shortly after we re-open to the public, Marianela de la Hoz’s summer residency will inspect real and mythical women in similarly revealing fashion. While Marianela’s paintings tend to be small, detailed, and vividly colored, her interest in narratives of female heroism connects her work directly to the Faubourg Saint-Marcel artisans. The title of the forthcoming exhibition--Destejidas (Unweaving)--takes its name the myth of Penelope, who wove a tapestry during the day and took it apart every evening as part of a strategy for keeping unworthy suitors at bay. During her residency, visitors can watch Marianela while she completes a painting on site. With the Artemisia tapestries hanging nearby, Marianela’s work provides an unexpected, but welcome reference point for reconsidering the place of women in art at the Timken.