Raphaelle Peale, Cutlet and Vegetables, 1816

It is open to debate, but I am not alone in thinking that perhaps the most beautiful of all early nineteenth-century American paintings is today in San Francisco: Raphaelle Peale’s Blackberries (c. 1813). It is a small, almost perfect work of art. A dish of freshly picked fruit, some unripe and still on the thorny vine, are placed in a low porcelain bowl that is set on a grey soapstone counter. The berries glint in delicate light that the artist closely observes, but most of the panel’s surface is cast in shadows. The painting once belonged to John D. Rockefeller, III but since 1993 it hangs in the M.H. de Young Museum along with almost 150 other works from that distinguished collection of American art.

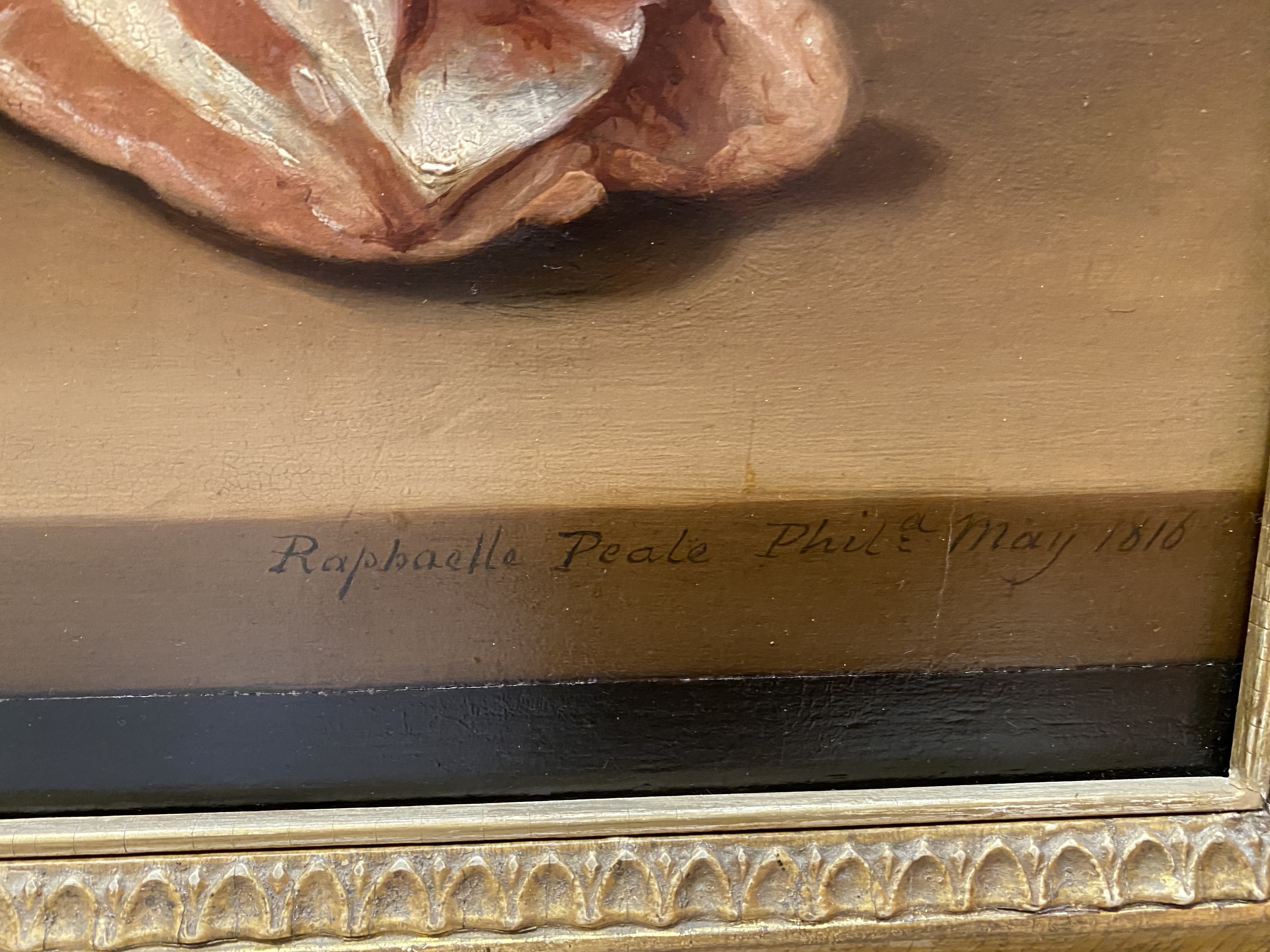

I first got to know Peale’s masterpiece when I was still a graduate student, serving as the National Endowment for the Arts Intern at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. I was fortunate to work for Marc Simpson, who was their curator of American paintings, and who established for me what remains a durable example of excellence in museum work. Shortly after being acquired by the Putnam Foundation, in 2000, the Timken’s leadership invited Simpson to analyze Peale’s Cutlet with Vegetables (1816). He called it “one of the artist’s most singular and ambitious panels.” In a now hard-to-find publication celebrating a handful of recent Timken acquisitions made around this time, Simpson--who also curated the Timken Museum’s landmark exhibition about Eastman Johnson’s Cranberry Harvest, Island of Nantucket--noted the work’s critical relationship to a series depicting cuts of meat arrayed with fruits and vegetables on kitchen counter planks. The artist made these in his hometown, Philadelphia. The Timken’s image is inscribed with both a precise date--May 1816--and its place of manufacture. Peale confronts us, phenomenologically and unbeautifully, with the sullen, obdurate present-ness of things. Indeed, Simpson connects this work to the sad biography of the artist; all of these paintings were made shortly before Peale’s death, in 1825.

This same image by Peale has also been vigorously explored by Alexander Nemerov in terms of its connection to “anatomized still life.” In his book, The Body of Raphaelle Peale: Still Life and Selfhood, 1812-1824 (2001), Nemerov associates Peale’s slightly morbid interest in butchered animal flesh with the rise of scientific illustration within Philadelphia’s medical community. Peale, whose family was firmly ensconced in the city’s elite culture, would have been aware of the latest advances in anatomical dissection and its representation in some recently published textbooks. It was only natural for the artist to bring some of that new graphic specificity back to his own still life practice. Nemerov keenly draws attention to the way that the raw onion stalks are treated like tendons in Cutlet with Vegetables. He ends up devoting an entire chapter in his book to the overlapping fields of medicine and art in early nineteenth-century Philadelphia. The Timken’s painting becomes a main character in that unexpected and well-told drama.

I conjure these two distinct interpretations of the same object because, when it comes to great works of art, it seems important to appreciate how more than one satisfying explanation is possible. Simpson and Nemerov happen to be two of the most gifted scholars that the field of American art has to offer. I am always interested in what they have to say about compelling objects. In the end, the “blackberries” painting in San Francisco will likely remain my favorite work by Raphaelle Peale. However, the work we have here in San Diego, while difficult for vegetarians to look at, is truly something to ponder and a marvel in its own lasting, visceral way.