Anonymous Russian Artist, "Literacy is the Path to Communism," c. 1920 (Duke University Libraries.)

.jpg)

Amy Putnam (1874-1958), the youngest of the three Putnam family members who founded the art collections at the Timken, was an ardent admirer of Russian culture. In 1918, Amy began her studies of Russian language and literature at Stanford University. That academic interest likely contributed to her later decision to collect Russian religious icons as a hobby. By one account, the private rooms of Putnam’s grand residence at Fourth and Walnut Streets in San Diego were covered with more than 300 of these mostly small-scaled works. Unfortunately, we don’t have a clear sense of what Amy’s older sisters--Anne and Irene--thought of the icons and their proliferation throughout the house. There is no question, however, that the room devoted to the Russian icons at the museum stands as the most faithful representation of Amy’s refined, highly individual taste. Even the green flocked wallpaper against which the glittering panels are set today is said to have been her choice.

Apart from being able to read some of the less-ornate Cyrillic script that appears on these intricate works, I have virtually no useful expertise when it comes to interpreting the Russian icons now in San Diego. The Timken has been fortunate, however, to rely on outside scholars to provide insights into this numerically significant part of its permanent collection. In 2017, Wendy Salmond, a noted scholar of late-Imperial Russian Art who teaches today at Chapman University, reviewed the entire collection and proposed a completely new installation of the works. Partly because that recently refurbished gallery is not currently available for public view, I want to underscore how improved the space seems and credit Dr. Salmond fully for this achievement. Her reinstallation plan includes a more robust interpretive framework for many of Amy Putnam’s favorite works, as well as some subsequent gifts to the museum. We are immensely grateful for her assistance with this project.

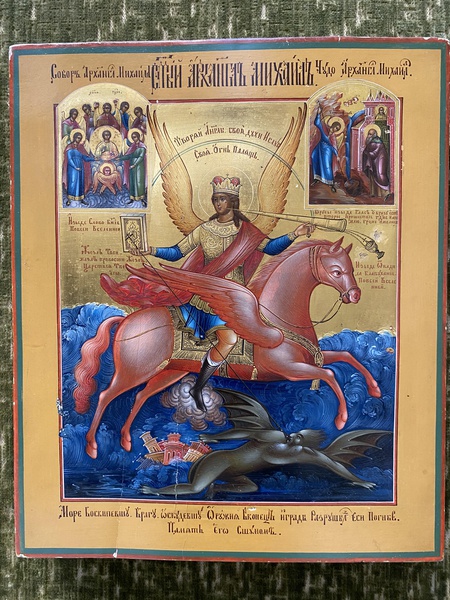

Let’s remember that Amy Putnam chose to launch her studies of Russian culture at the outset of the Bolshevik Revolution, which began in October 1917. Because the Soviet propaganda machine made canny use of familiar imagery, her professors at Stanford must have been alert to the ways in which Orthodox religious iconography was being actively retooled for new ideological purposes. Did Amy consider any of these problems while reading the novels of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky? Her appreciation of small devotional works, like the one celebrating the triumph of Archangel Michael over a demon, or truth trampling evil, is noteworthy. But what would she have thought about an anonymous Russian revolutionary artist’s conversion of that Orthodox iconography into a message that “Literacy is the Path to Communism”? Amy’s awareness of the contemporary “culture wars” that stood behind her beloved study of things Russian might have made for lively dinner table conversations with her older sisters. I only wish we had the advantage of sitting in on one of those evenings. Even a single opportunity to eavesdrop would cast tremendous light on the motivations of these indisputably cultured, yet fundamentally mysterious (to us) women.